The Brief History of Ultralight Hiking & Cottage Manufacturers in Japan Vol. 1

The Brief History of Ultralight Hiking & Cottage Manufacturers in Japan Vol. 1

This month Journal’s theme is “UL Hiking.” With that in mind, I, Mita, the editor-in-chief of Yamatomichi Journals, would like to take this opportunity to re-publish a column titled “A Brief History of Japanese UL & Garage Manufacturers” that I once wrote for the magazine ‘Wonder Vogel’ (published by yamakei magazine).

Originally, this column was created as a text version of the material I compiled for a talk show held in Kyushu’s Kujū in 2016. The narrative ends there, but for those familiar with the subject matter, it will evoke a sense of nostalgia. For those who have only recently become interested in this world, it may present an entirely unknown realm. It’s a piece that, even upon re-reading, elicits a curious sense of wonder.

There are actually many more figures and epic moments to cover, but I have, albeit presumptuously, chosen to present it in this format for now. I’m planning to continue this series as “Volume 1” in order to feature more characters and developments that have emerged since then. If you’re intrigued, please don’t hesitate to send a message!

Introduction

Allow me to take you on a journey into the world of Ultralight Hiking in Japan.

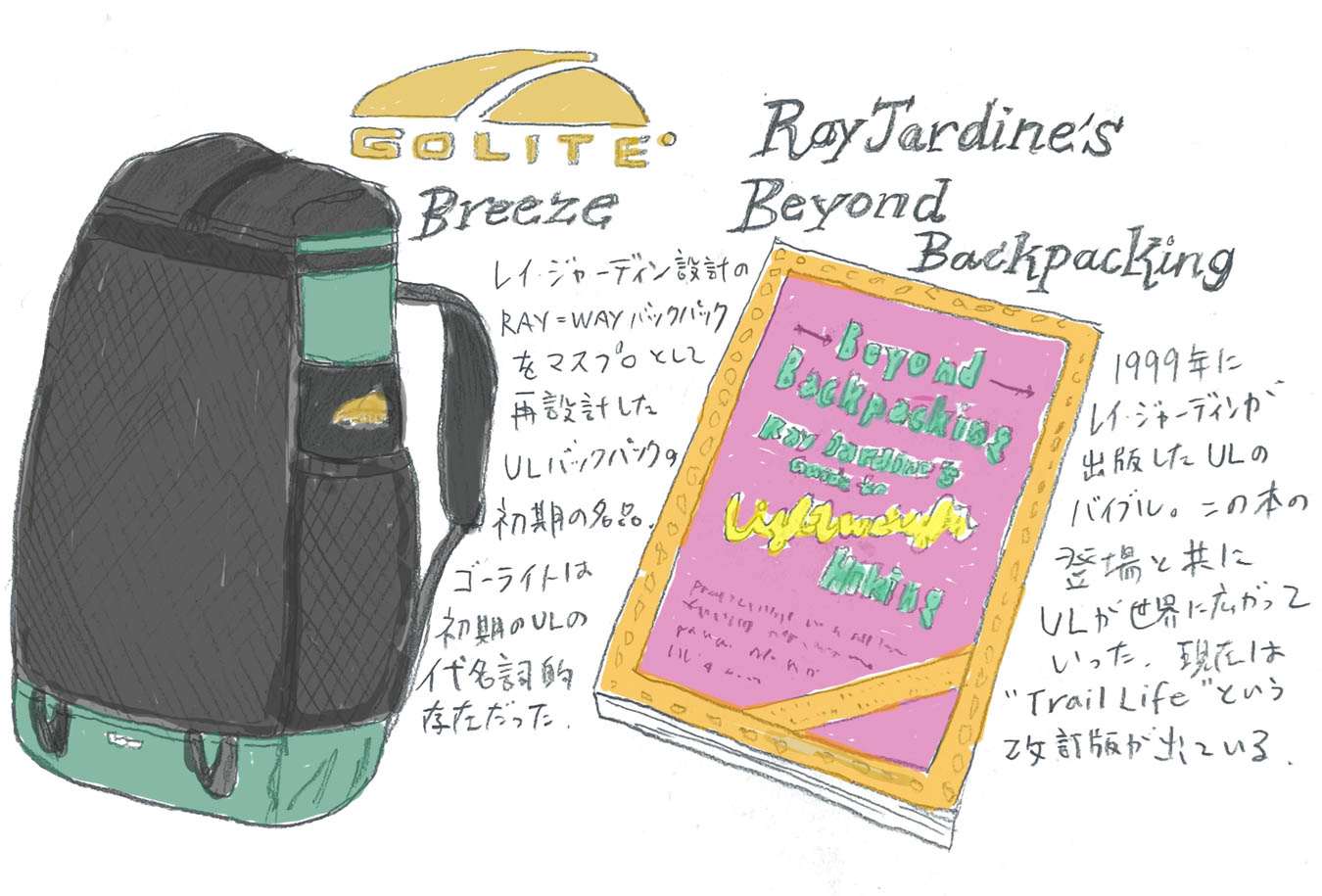

Ultralight Hiking, often abbreviated as “UL,” is a methodology of lightweight mountaineering that emerged from the community of thru-hikers traversing the long trails of America in the 1990s. It all began to coalesce when Ray Jardine, in his 1999 book ‘Beyond Backpacking,’ formalized this approach. It quickly spread across the globe, found its way to Japan in the early 2000s, and has since been quietly shaping its own niche alongside the mainstream mountaineering scene.

UL is not merely a methodology; it’s a philosophy, a culture, and at times, it can even transform lives. In fact, I know several individuals who’ve been profoundly affected by this way of thinking, and I might be one of them. Today, I want to share their stories. I want to delve into how the UL culture crossed oceans and evolved into what it is in Japan today. What events transpired, and whose passions drove it? I believe that, in this era of an expanding UL scene, it’s crucial to reflect upon these beginnings.

Salt Lake City in the summer of 2000

The origins of Ultralight (UL) hiking in Japan may be shrouded in differing opinions, but for me, the story unfolds in the sweltering summer of 2000, amidst the grandeur of Salt Lake City, USA, where the annual Outdoor Retailer Show took place. At that time, Tatsuya Tsuchiya, who currently owns “Hikers Depot” and then served as a buyer for an outdoor shop, stood before the booth of the now closed UL manufacturer, GoLite.

As he gazed upon the display of frameless rain covers and featherweight backpacks, and flipped through the pages of Ray Jardine’s ‘Beyond Backpacking,’ Tsuchiya felt a seismic shift within himself. He recalls being struck with a thunderbolt of inspiration, thinking, “Could it be that by adopting this approach, one could witness entirely new world of hiking? Until then, I had esteemed the value of ‘doing what no one else could do,’ but now, the notion of ‘anyone can do it’ felt wondrous. Isn’t ‘walking’ the very essence of it all?” (*1)

This moment, when Tsuchiya crossed paths with UL, turned out to be a source of immense joy for him and a turning point for the Ultralight movement in Japan. Tatsuya Tsuchiya, a man deeply versed in outdoor culture, possessed an unparalleled passion for shaping cultures and scenes. Without such dedicated individuals, it’s possible that Japan’s Ultralight culture might never have come into existence. Or even if it had, it might have faded into obscurity long ago.

The Blog Age

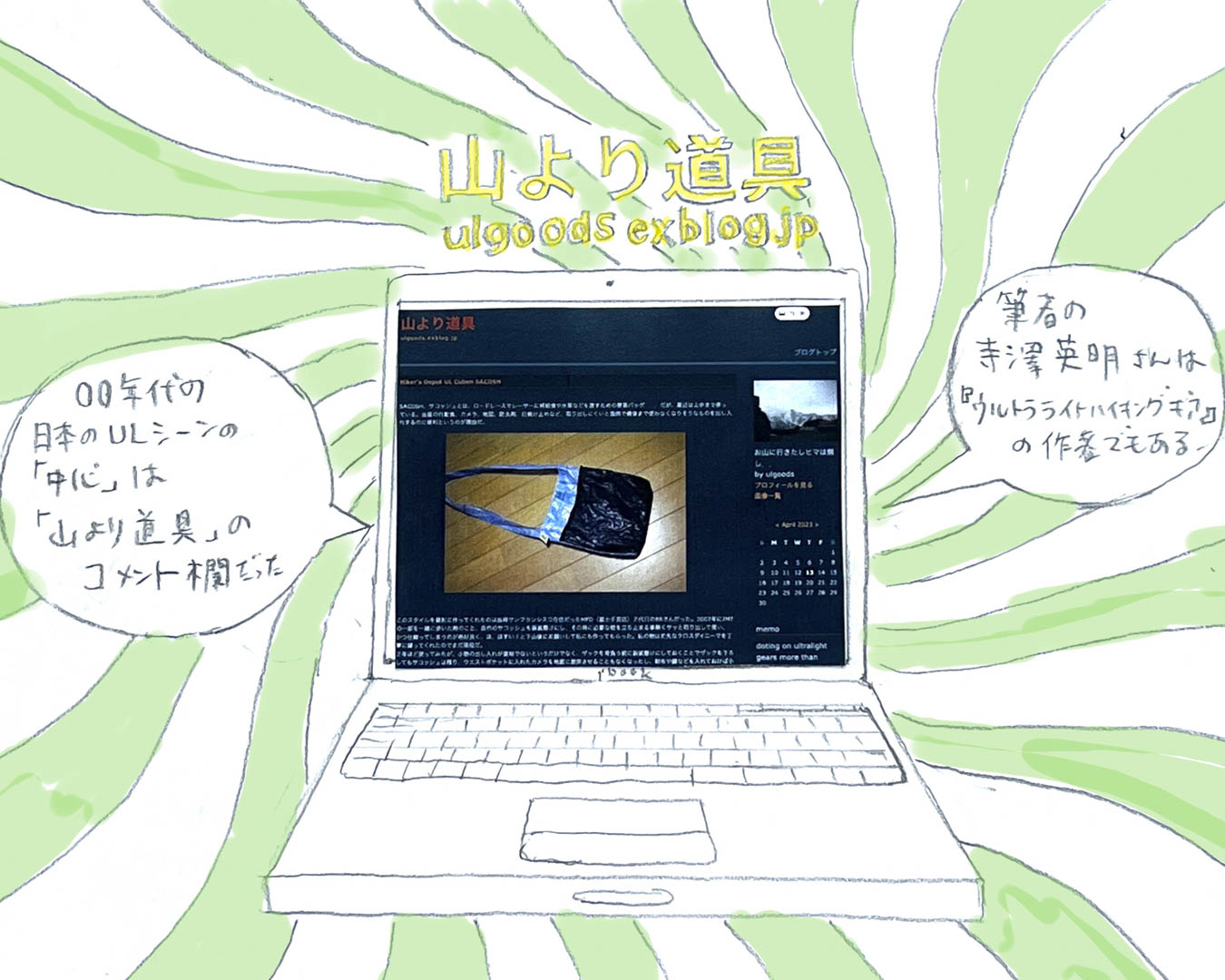

In the early 2000s, within the quiet corner of the ODBOX Annex store in Ueno, where Tatsuya Tsuchiya was employed at the time, UL gear quietly made its debut. During those days, Ultralight (UL) information was not readily available in magazines. Instead, a handful of dedicated enthusiasts, far removed from the mainstream, maintained blogs and websites. These platforms showcased reviews of gear from obscure manufacturers that most had never heard of. Armed with these reviews, they ventured into the mountains, sharing tales of shivering through cold nights and enduring torrential rains.

Among these pioneers, one blog, “Yama Yori Dougu” by Hideaki Terazawa, stood out in terms of quality, quantity, and the speed of information dissemination. In an era before social media had consolidated all information, the comments section of “Yama Yori Dougu” became a hub for hikers to connect, gradually forming a community. Reflecting on that time, Tatsuya Tsuchiya and Hideaki Terazawa had a conversation in 2015:

Tsuchiya: “Looking back, it was like we were all struck by a fever. In hindsight, it was kind of like ‘chuunibyou’ (adolescent delusions of grandeur), wasn’t it? (laughs).”

Terazawa: “I felt a kind of self-imposed mission, like, ‘If we don’t spread this new methodology to the world, who will?’ We often talked like that, didn’t we?” (*2)

In an era where mainstream media hardly covered UL, every hiker scoured UL-focused blogs nightly, checking for fresh insights and experiences. Though I was merely a bystander at the time, the birth of a hiker-to-hiker scene, entirely distinct from the traditional outdoor industry, filled me with a dizzying excitement.

Amidst this fervor, Tatsuya Tsuchiya eventually made a momentous decision: he would strike out on his own. In 2008, he opened “Hikers Depot,” Japan’s first – perhaps at the time the world’s only – dedicated UL gear store in Mitaka, Tokyo. The establishment of a physical store for UL was an earth-shaking event. It provided a tangible “space” to a world that had previously existed mainly within the confines of the internet.

Hikers Depot’s storefront and the events it hosted, like the “Hikers Party,” became hubs for hikers to connect and foster the burgeoning UL scene. It was here that people met and collaborated, laying the foundation for an exciting new chapter in the world of hiking.

The Age of Alcohol Stoves

During that era, the heart of the UL community was focused on homemade alcohol stoves crafted from modified aluminum cans. These DIY alcohol stoves, which could be lighter and, with some ingenuity, more powerful than store-bought versions, became symbolic of UL. Numerous UL-focused blogs showcased their homemade creations and shared instructions on how to make them, all using discarded aluminum cans that would typically be considered trash.

The world of DIY stoves, which demanded both scientific knowledge and dexterity, seemed to resonate with the Japanese sensibility. It gave rise to creations that often outshone their American counterparts. This scene eventually led to the birth of T’s Stove, a garage-based manufacturer specializing in alcohol stoves founded by Toshihisa Tsukagoshi. T’s Stove gained enough recognition that its products were even sold in the United States.

The wave of DIY gear-making, ignited by stoves, soon extended beyond stoves to encompass backpacks, tarps, and more. It led to the emergence of a series of garage-based manufacturers. One person who embodied the spirit of that era was Junichi Takahashi of FreeLite. It all began when he started selling DIY gear that had garnered positive reviews on his blog (at the time, under the name MLV Factory). Today, FreeLite has grown into a comprehensive manufacturer, offering a range of products from backpacks to shelters. If you’re interested, you can still find some of the early blog entries from FreeLite that showcase the gear he was creating.

But perhaps the defining moment came in 2009 with the emergence of Locus Gear by Johtaro Yoshida. While there were manufacturers like T’s Stove crafting small items like stoves and pouches, Locus Gear was the first full-fledged garage-based manufacturer to produce large items like tents. It was a milestone that made many think, “Japan’s UL scene has truly arrived.”

Yoshida also made a significant contribution to the scene by launching an online shop called ‘Outdoor Material Mart’ simultaneously with Locus Gear. This shop provided specialized materials required for UL gear, significantly lowering the barrier for amateurs to create their gear. Reflecting on the atmosphere of that era, Yoshida stated:

“The UL movement had a counter-cultural vibe distinct from traditional outdoor activities, and I resonated with it. Terazawa’s blog and Tsuchiya opening his store in Mitaka were undoubtedly pivotal. With many like-minded enthusiasts around, there was an atmosphere of ‘If they can do it, why can’t we?'” (*3)”

The Rise of Amateur UL Enthusiast

In 2010, Chiyoda Takafumi and Komine Hideyuki, the founders of Moonlight Gear, opened their online shop. With time, they actively introduced overseas manufacturers and small domestic garage-based manufacturers that weren’t readily available in Japan. Gradually, Moonlight Gear established itself as another hub in addition to Hikers Depot.

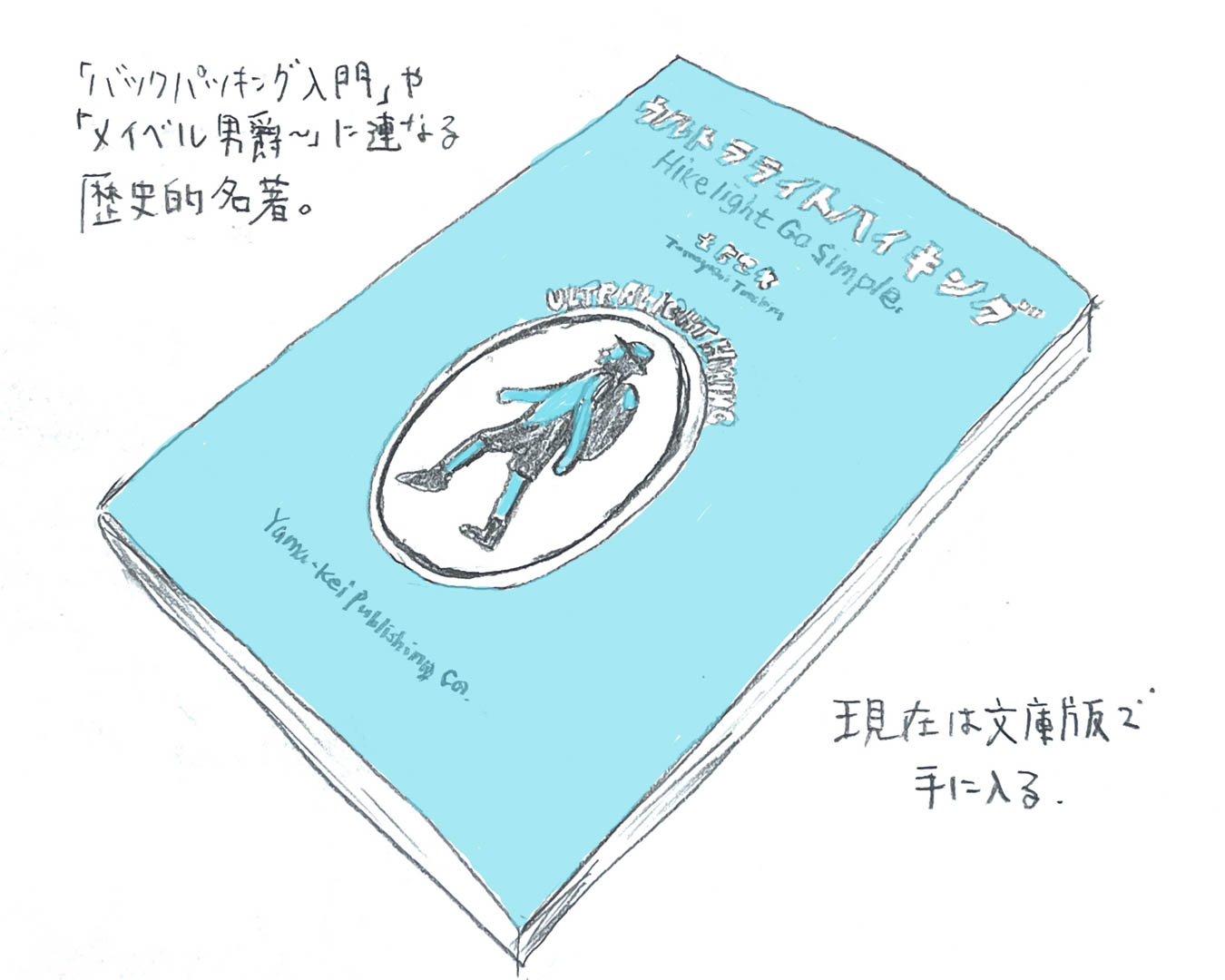

In 2011, Tatsuya Tsuchiya published his book, “Ultralight Hiking,” with YamaKei publishers. While it served as a textbook-like guide to the fundamental principles of UL, Tsuchiya’s foresight in not creating a mere gear catalog but focusing on explaining UL’s foundational methodology is admirable. Thanks to this, even five or ten years later, this book would continue to serve as a guiding light for those stepping into the world of Ultralight.

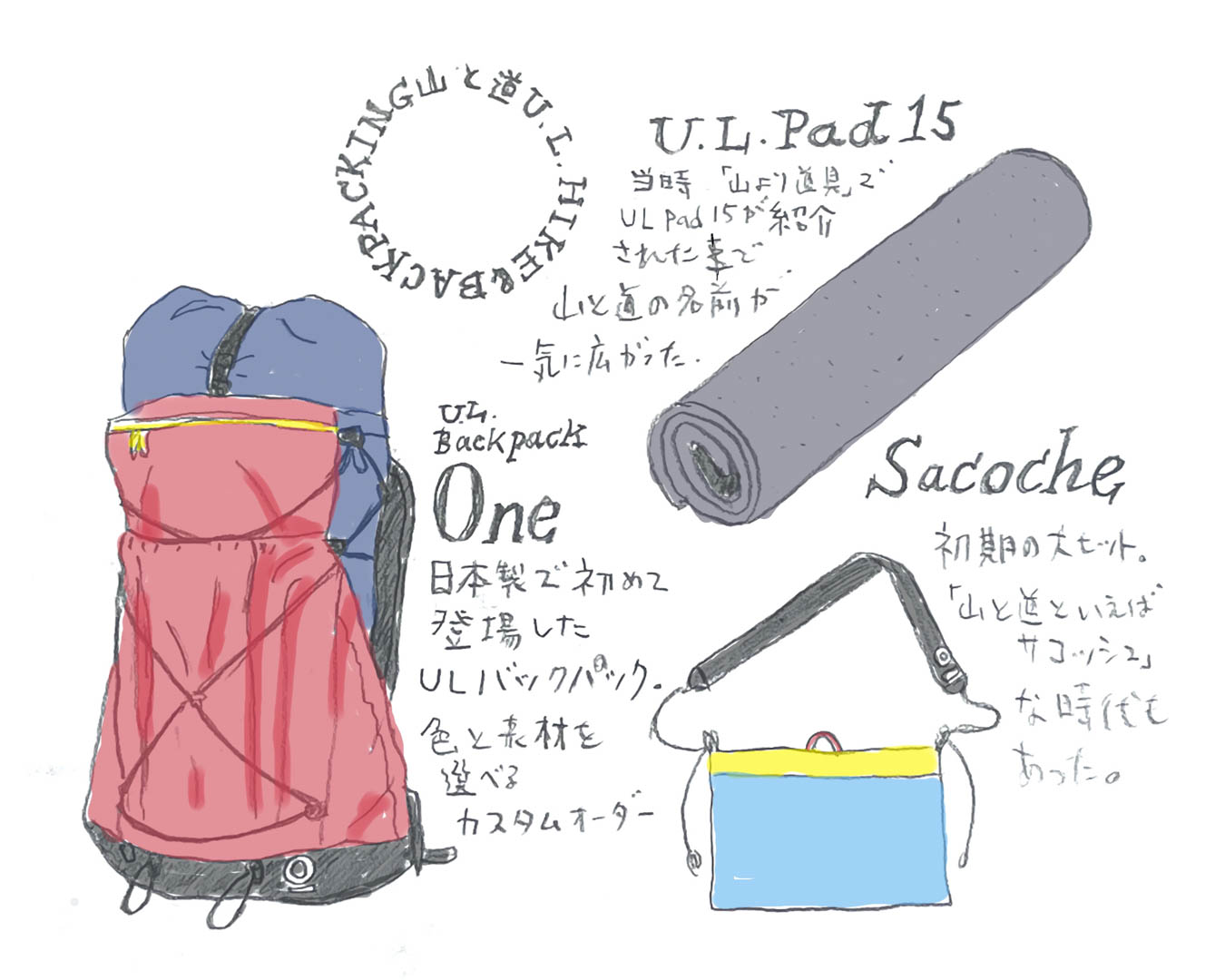

During the same year, Akira Natsume and his wife Yumiko’s started Yamatomichi. Which bursted into the scene with the world’s lightest closed-cell foam sleeping pad. Their backpacks, which followed shortly after, possessed a unique originality distinct from American UL backpacks. Additionally, their colorful pouches garnered popularity beyond the UL scene. Akira Natsume, who had built a career in the worlds of design and art before venturing into outdoor gear, quickly elevated “Yamatomichi” to a prominent position within the scene. Reflecting on the initial aspirations of their business, Natsume states:

“I strongly resonated with the DIY aspect of UL hiking gear. ‘Maybe I can do something too,’ I thought.” (*4)

Notably, whether it’s Akira Natsume, Johtaro Yoshida of Locus Gear who formally worked in the food business, Chiyoda and Komine of Moonlight Gear who had formal office jobs, or even Tatsuya Tsuchiya, who had worked as a store clerk at an outdoor gear shop, none of them originally hailed from the outdoor industry. They were all “amateurs” from entirely different fields. It’s intriguing how these individuals, unified by the motto of UL, jumped into this world, shaping the scene and gradually gaining a presence that the mainstream outdoor “industry” could not ignore. Without the UL culture, it’s highly likely they wouldn’t have ventured into this realm. From their inception to the present day, it has been a culture built consistently by hikers themselves rather than mainstream manufacturers or media.

The future of UL

In 2012, Hikers Depot organized the “Hikers Party,” a gear-making contest with the theme “MYOG (Make Your Own Gear) World.” This event introduced a fresh wave of creativity to the UL community. In 2013, from among the participants in the Hikers Party, two notable garage-based manufacturers emerged – Ogawa Tatsuyuki with “Ogawando” and Awasu Hajime with “Wonderlust Equipment.” The people who gathered at the Hikers Party had now become players in the field. Ogawa and Awasu co-founded the workshop and shop “Mt.FABs” in 2014, which not only produced gear but also served as a showroom for products from other young garage-based manufacturers in the area. Together, they became leaders of the “second generation” of UL makers.

During the same period, manufacturers began emerging from outside the established UL scene. Atelier Blue Bottle, founded by Kei and Rina Tsujioka, who had previously worked as bag designers, rapidly gained recognition for their craftsmanship and unique sense of design. They created a separate scene within the UL movement that was distinct from the trends mentioned earlier.

In 2015, a joint exhibition and sale event called “Off the Grid” brought together alternative manufacturers and distributors, with a focus on garage-based UL manufacturers that had emerged in recent years. Over the course of two days, this event attracted a total of 3,000 visitors, reaffirming the high level of interest in the UL scene. The number of garage-based UL manufacturers that have emerged in recent years can’t even be counted with both hands.

In 2016, Yamatomichi opened Yamashokuon, a gear shop and restaurant in Kyoto. Manufacturers born from the UL scene, which was once just a blog bassed community, finally had physical storefronts. Ray Jardine, “the” pioneer of Ultralight hiking, visited Japan in autumn and hiked along the San’in Coast Trail with Tatsuya Tsuchiya, Akira Natsume, and other individuals who had played key roles in shaping Japan’s UL scene. It was an event that marked both the end of one era and the beginning of another.

Ray Jardine visited Japan in 2016 and walked the San’in Coast with Tsuchiya, Sanpo of Sanpo’s Fun Lite Gear, Yama to Michi Natsume, the author, and many other hikers at an event held in Tottori.

Five years ago, in 2011, during an interview I conducted with Tatsuya Tsuchiya, I asked, “What would you like to see in the UL scene in five years?” Tatsuya replied, “I hope there will be more garage-based UL manufacturers in Japan.” Looking back now, it seems that at the time, this was merely a hopeful vision for Tatsuya, something he didn’t really expect to come to fruition. However, five years have passed, and it has become a reality, a remarkable transformation. When asked the same question about the UL scene in ten years, Tatsuya had this to say:

“In ten years, I hope that UL will be normalized. I’d like to see a state where everything from traditional style to ultralight is embraced, and we can all say, ‘Even if we have different styles of hiking, we are all hikers.’ After all, hiking is a fundamental activity that anyone can do, and isn’t UL just a return to the roots of humanity, the timeless act of walking and traveling? It’s something that, as we’ve seen, can sometimes change people’s lives.” (*1)

(*1) 2011 From an interview by the author in the magazine Spectator

(*2) From a conversation with the author in the web magazine TRAILS, 2015

(*3) Unused portion from an interview by the author in Peaks magazine, 2015

(*4) 2011 Interview by the author from https://www.yamatomichi.com/journals/4415

first appearance; Wonder Vogel, Feberary issue, 2017 by Yamakei Publishers.