HIROKO MIHARA “Eating” #1

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

HIROKO MIHARA “Eating” #1

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

In the HIKING AS LIBERAL ARTS series, hosted by Hideki Toyoshima, Yamatomichi HLC (Hike Life Community) director, we consider hiking as a liberal art, a field of study that liberates individuals from preconceived notions and norms, empowering them to act based on their own values. This series delves into physical aspects of hiking –– seeing, hearing, eating –– for clues to exploring the value of and potential that extends beyond hiking.

Our third guest of the series is Hiroko MIhara, who runs Nanpūshokudō, a culinary business, with Rika Koiwa. Hiroko is well-versed in shokuyōjō — the practice of nourishing both body and mind through diet –– and her work draws on traditions such as Ayurveda, macrobiotics and Chinese medicine. Our conversation explores how eating is linked to our physical and mental wellbeing and the social fabric that binds us.

Interview Notes: Hideki Toyoshima

Our first guest in the series, Roger McDonald, broadened our understanding of “seeing,” and our second, Yoshiaki Nishimura, deepened our capacity for “listening”. With our third guest, Hiroko Mihara, we turn our attention to eating.

Eating serves a biological purpose: to nourish our bodies and maintain our health. Yet it also has sociological significance. Across eras and cultures, shared meals — with family, friends, colleagues — have always been important for creating connections. Convening over food remains central to how we exchange ideas, stories and information. As hikers, we know firsthand how special it feels to sit around a campfire, eating with our traveling companions after a long day on the trail. With Nanpūshokudō, Hiroko not only prepares meals; she also creates a place for people can come together over food.

Hiroko Mihara Chef. Co-head of culinary business Nanpūshokudō. Her food-related work spans event planning, recipe development and menu direction for restaurants. She is a BSS-certified Ayurvedic therapist and an International Chinese Medicinal Food Specialist. Hiroko also teaches a workshop on Ayurvedic lifestyle practices and cooking. Instagram:@nanpushokudo

Shokuyōjō (nourishment through food)

ーー I’d like to talk about how eating serves two roles: sustaining life and building society. Could you start by introducing yourself and telling us a little about what you do?

I have jointly run Nanpūshokudō with my business partner since 1999. Our work is wide-ranging: catering, recipe consulting for restaurants and recipe writing for online media and magazines. About 15 years ago, I became interested in shokuyōjō —– the practice of using food to maintain and improve health —– and as I went deeper into it, my lifestyle and activities changed.

ーー Could you explain what shokuyōjō actually is?

Shokuyōjō refers to using food as a way of maintaining a healthy and comfortable state of mind and body and addressing imbalances and health issues. There are many different traditions of shokuyōjō. For instance: traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), and Wakanpō, a system that adapted Chinese medicine to Japan’s seasons and to the Japanese physiology. There’s also Ayurveda, which originated in India, and macrobiotics, a philosophy proposed by George Ohsawa (*1). Some people base their practice on these systems; others incorporate local herbs or traditional food customs unique to their own regions.

Around 15 years ago, I had the opportunity to work on a project related to macrobiotics. I felt that just understanding the theory and cooking accordingly wasn’t enough — I wanted to study it properly. I began by learning Chinese Medicine and macrobiotics. Later, I started discussing with an Ayurvedic teacher the idea of creating a class together. We spent about a year developing a program that incorporated Ayurvedic lifestyle practices and diet, and eventually launched a cooking class. At that time, I was still very much a beginner when it came to Ayurveda, but this year marks the tenth year since we started the class. Over that period, I have continued my studies –– at schools in Japan and institutions in India –– to deepen my understanding of Ayurveda.

(*1)George Ohsawa (1893ー1966)

Japanese philosopher and founder of the macrobiotic movement. Ohsawa developed macrobiotics as a dietary practice centered on traditional local foods and grains, drawing from Eastern philosophies such as I Ching and the concept of yin and yang. Ohsawa’s real name was Nyoichi Sakurazawa, and in Japan he is commonly known as Yukikazu Sakurazawa, one of several pen names he used while living in Europe.

―― I’d like to hear about the different forms of shokuyōjō that you studied, starting with Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). What exactly is TCM?

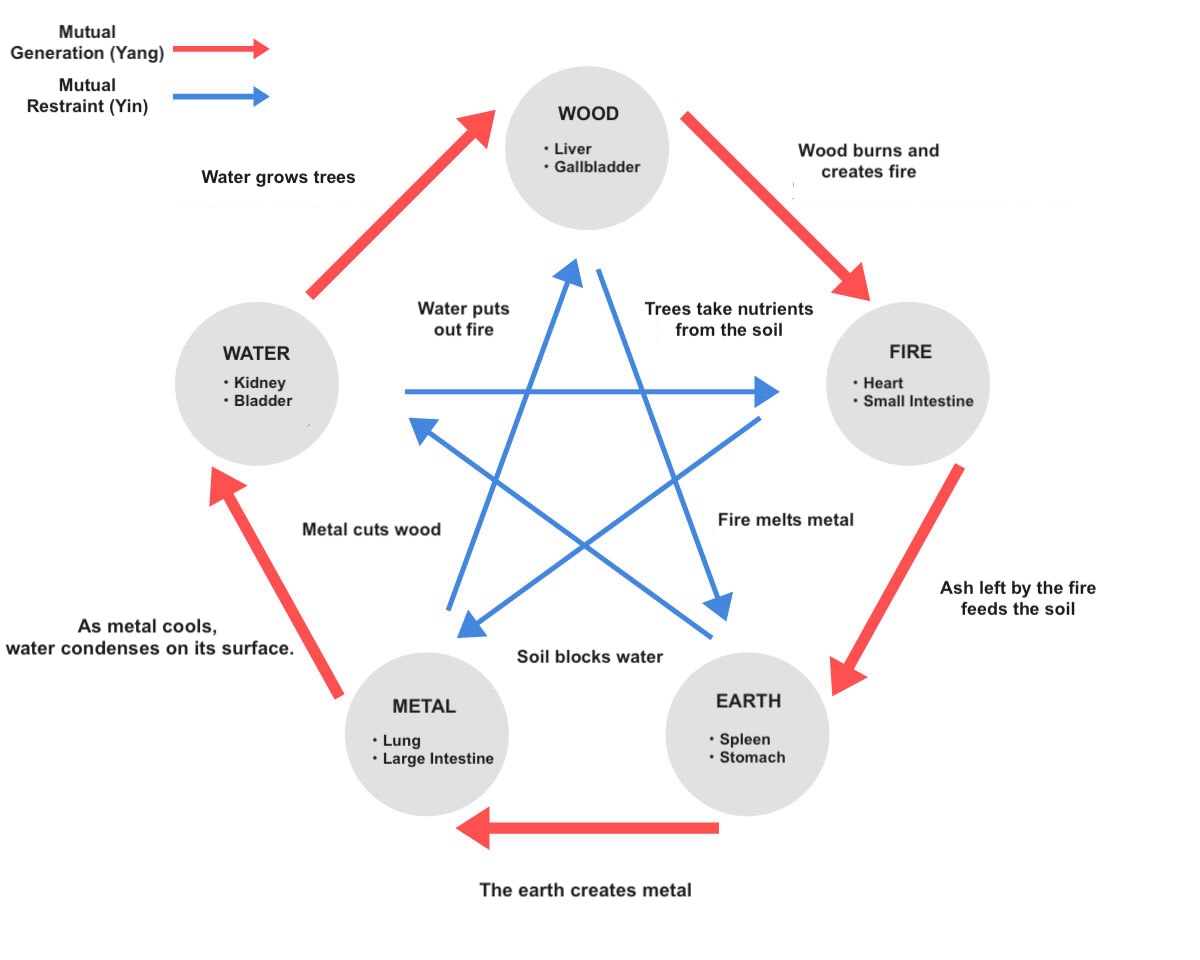

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is a medical system that has been practiced in China for over 2,000 years. It views a person’s environment and internal balance the same way it observes the natural world. The goal is to identify and address the underlying causes of illnesses that arise from imbalances, and to prevent disease. TCM is based on theories such as the Yin-Yang Theory and the Five Elements Theory. Under the concepts of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, everything that exists embodies opposing yet complementary forces (yin and yang), as well as five intrinsic qualities (the five elements). Among the five elements, some are compatible, some incompatible. When I attended a TCM school, the very first thing the teacher said in class was this: “In TCM, we apply the same scale of measurement to understanding the universe, building a city and the workings of the human body.” Hearing that got me incredibly excited. I felt as if I was about to touch on a universal principle or secret of the world that I had never encountered before.

―― Could you explain more about the Five Elements?

The philosophy holds that everything on Earth is made up of five elements: wood, fire, earth, metal and water (mok-ka-dō-kon-sui). There’s a cycle involving the elements that repeats endlessly. Wood burns to create fire. Fire burns out and becomes earth (ash). Earth condenses and produces metal (minerals). Metal cools and generates water. And water nourishes and grows wood again. Everything in nature –– and everything that makes up the human body –– can be classified according to these five elements. The four seasons, organs, colors, grains, behaviors, moods and flavors all correspond to the five elements. For the body’s internal organs, the liver corresponds to wood, the heart to fire, the spleen to earth, the lungs to metal and the kidneys to water.

When you experience physical discomfort –– eye pain or sensitivity to cold –– Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) can be incredibly helpful. Let’s say you’re feeling cold in winter. You would focus on warming the kidneys, which correspond to the element water in the Five Elements theory. You might also eat foods associated with water, such as pork or beans. Starting from just one key idea, TCM offers a wide range of practical solutions, which makes it very easy to apply. In TCM, there’s an emphasis on the concept of preventive medicine (meibyo). By incorporating food and practices aligned with the seasonal elements daily, you can maintain a healthy balance of body and mind.

ーー I heard that you also studied macrobiotics. What do you think of it?

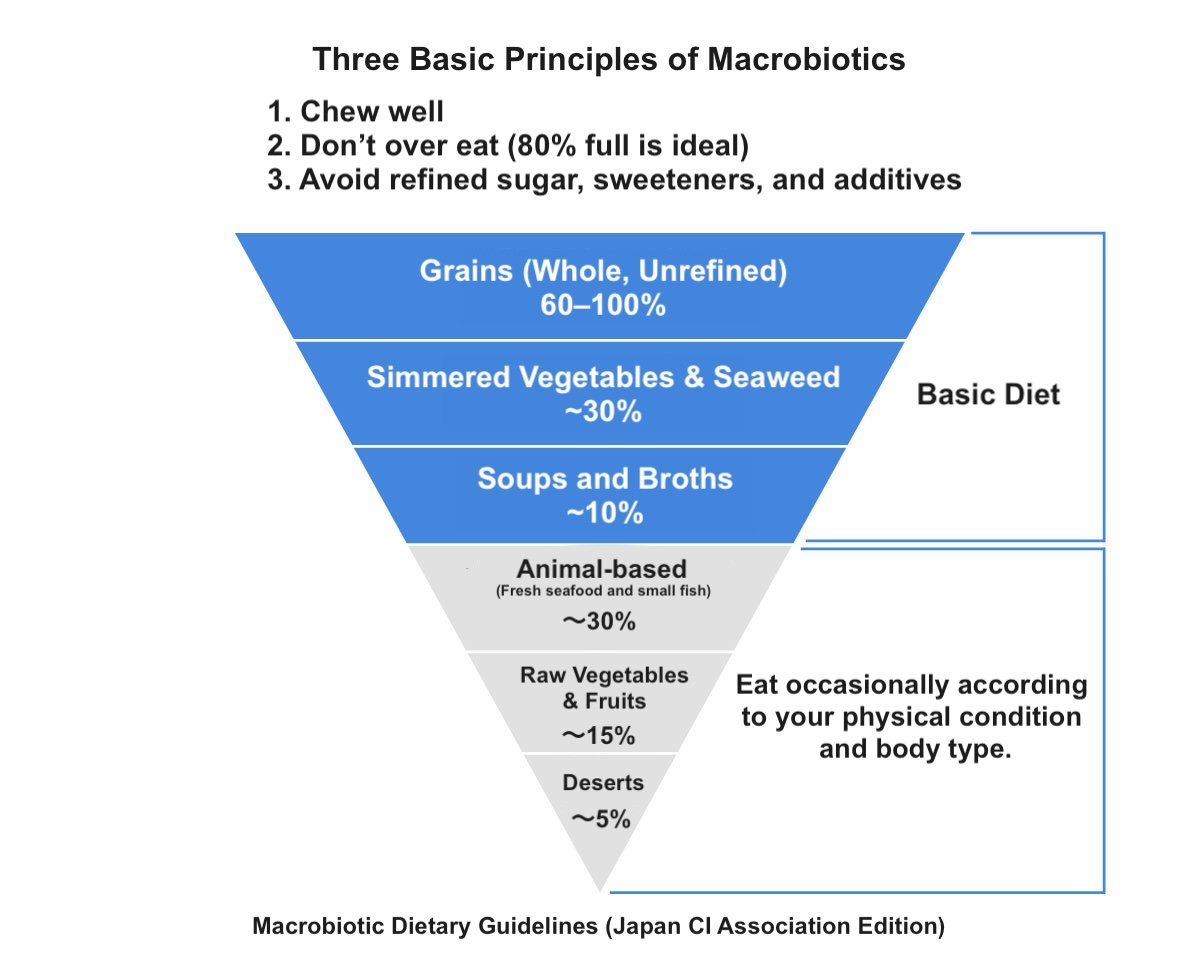

Macrobiotics is an approach to diet and lifestyle that’s centered around vegetables, seaweed and grains. It’s based on balancing the yin and yang properties of food and on principles such as Shindofuji (the unity of body and land) and Ichibutsu Zentai (the whole of an organism). Shindofuji means eating food grown in the region where you live, while Ichibutsu Zentai expresses the idea that every kind of food is a whole, living entity and should be eaten in its entirety. When eating vegetables, you use everything — skin, stems, roots — so you’re not wasting anything.

Before studying it properly, my impression of macrobiotics was that it had a lot of strict prohibitions. When I met people practicing it, they would say things like, “You can’t eat anything but brown rice,” or, ”no meat,” or, ”no sugar.” It seemed very rigid and harsh, and I felt like it would be hard to adopt. But when I actually decided to study the theory and read George Ohsawa’s books, I realized that none of what I was hearing about macrobiotics was actually written in his texts. Instead, I found a very flexible philosophy, one that spoke of seeing the world through a universal lens. It made me much more interested in his ideas.

Macrobiotics in Japan began in the late 1920s. Back then, diets were much simpler, and malnutrition-related illnesses were common. But today, we live in an age of overabundance — everyone eats plenty of meat, and people’s bodies tend to be more yang — so we live in a very different time from that period. Which is why I wanted to learn from teachers who were thinking about how to adapt macrobiotics to today’s reality. I read many books and sought out different voices. Eventually, I discovered Kenji Okabe (*2) in Fukuoka, a city in southwestern Japan. In Okabe’s classes, I learned about seasonal ingredients and cooking methods, approaches to daily living aligned with nature, and bōshin-jutsu — the art of diagnosing physical imbalances by reading the face and body.

(*2)Kenji Okabe

Born in 1961 in Gunma prefecture, Okabe is the director of the Japan Brown Rice and Whole Food Research Institute and a food and medical consultant. While studying abroad during college, he was shocked by the high rates of obesity in the U.S., which led him to realize the value of Japan’s traditional diet as the ultimate form of healthy eating. After encountering the macrobiotic philosophy of George Ohsawa, he opened the Japan Brown Rice and Whole Food Research Institute in 2003. He continues to travel across Japan giving lectures and health guidance on macrobiotics.

―― It seems that both macrobiotics and Traditional Chinese Medicine are not just about food but also incorporate broader ways of thinking. Are they similar?

I feel that Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and macrobiotics are very closely related. TCM is a method of maintaining health suited to China’s seasons and natural environment, and macrobiotics concepts like Shindofuji (the unity of body and land) and Ichibutsu Zentai (the whole of an organism) are also part of TCM teachings. Ohsawa was influenced by Sagen Ishizuka (*3), who promoted shokuiku (food education) and had studied Kanpō —Japanese herbal medicine that developed from the foundations of TCM after it was imported from China. I think macrobiotics — with its focus on yin-yang balance and its deep exploration of diets and lifestyles suited to people as living organisms and the environments they inhabit — can be seen as a refined and evolved form of that tradition.

(*3)Sagen Ishizuka (1851–1909)

A military doctor and pharmacist who was active beginning in the latter half of the 19th century, as Japan transitioned from the medieval Edo period, during which the country was closed off to the outside world, to the Western-influenced Meiji Restoration. Born into the family of a town physician in Fukui, western Japan, Ishizuka studied medicine. He noticed a link between food and health, and developed a theory, becoming the first in Japan to promote shokuiku (shoku means food, iku means education) — educating children about the importance of a proper diet on their bodies and minds.

Maintaining balance through Ayurveda

―― After that, you also studied Ayurveda. Can you explain what that is?

The earliest Ayurveda texts are said to date back to around 800 BCE. The word comes from Sanskrit: Ayur means life, vitality or longevity, and Veda means knowledge, wisdom or science. Ayurveda is a compilation of wisdom to help people live a healthy existence, mentally and physically. Its roots go back more than 5,000 years ago in India. It’s one of the world’s four major traditional medicines, and in India and Sri Lanka, it is officially recognized as a national medical qualification. India has Ayurvedic medical universities where students study for six years and then qualify as licensed Ayurvedic doctors, so it’s a respected medical tradition that exists alongside Western medical practices.

Many people may already be familiar with Ayurvedic treatments that use oil and herbs, such as Panchakarma, Shirodhara and Abhyanga (oil massages). But Ayurveda also places great importance on diet, the rhythms of the seasons and daily life and the balance between activity and rest.

What I find wonderful about Ayurveda is that it’s full of wisdom that feels very close to daily life –– almost like the kind of advice a grandmother might give. For example, there are easy-to-incorporate practices like detoxifying through a combination of oil massages and sweating, drinking warm water (sahyud) or rubbing chilled areas of the body with silk gloves when your body feels cold and heavy in winter. Ayurveda offers many simple methods for finely tuning the body in everyday life, which I find fascinating.

―― Ayurveda has the concept of the three body types, right?

Yes, Tridosha –– tri means three, and dosha refers to life energies or body types. The three qualities in Ayurveda are: Vata, which is associated with the qualities of wind; Pitta, which is associated with fire; and Kapha, which is associated with water and earth.

These three energies exist in everything –– seasons, people, food, times of day, tastes, landscapes –– and they are considered fundamental elements of the world. For instance: People with a lot of Vata tend to be light, quick and good at connecting people. They often enjoy traveling and meeting new people; and tends to be very knowledgeable. But they also tend to dislike stability, tire easily and experience emotional ups and downs.

People with a lot of Pitta are natural leaders, decisive and have the energy to drive things forward. They are often passionate and have a strong sense of justice. On the flip side, they may become forceful with their opinions or get angry when things don’t go their way.

Those with a lot of Kapha are steady and move through things at a relaxed pace. They can continue doing the same things without difficulty and find joy in routine. But they may also become overly introverted or find it hard to take action.

Everyone has one or two dominant doshas, and when the tridosha are in balance, the body and mind remain healthy. Ayurveda teaches that an imbalance of the doshas leads to illness.

―― How do you maintain balance in your body according to Ayurveda?

There are many factors that can disturb this balance: seasonal changes, diet, lifestyle habits, interpersonal relationships, actions and even emotions. In my classes, we first focus on recognizing the symptoms and physical changes that arise when a dosha is disturbed. Students learn to closely observe themselves. Then, we work on adjusting daily habits, diet and self-care practices to calm and balance the doshas that may become destabilized.

A measuring stick for understanding the body

―― Do you mix and selectively use Traditional Chinese Medicine, Macrobiotics and Ayurveda, depending on the situation?

Yes. Traditional Chinese Medicine’s (TCM) Yin-Yang and Five Elements theories, Macrobiotics and Ayurveda –– each of these serves as a kind of measuring stick for understanding the body and maintaining balance. I personally find Ayurveda especially easy to incorporate into my daily life because I can often feel the effects immediately. It’s also easier for self-care.

With TCM, including Chinese herbal medicine, there are many ways to address minor physical imbalances as they arise. I also make a point of always being aware of the Five Elements. As for Macrobiotics, while it would ideally be a daily form of self-care, I personally use it more as a dietary therapy when I start to feel a physical imbalance. I would say that my approach is to base my daily life primarily on Ayurveda, while also incorporating the best aspects of TCM and Macrobiotics.

My Ayurveda classes are now in their tenth year. At one point, when one of my students was feeling unwell, I taught a class on meals designed to suppress Vata symptoms –– meals aligned with the Vata season (when the wind element becomes dominant). After the class, the student said, “After eating the meal during the class, walking home felt so much easier, and that night I slept so well and woke up feeling completely different the next morning!” Just recently, another student who graduated from my class told me that by putting lessons into practice lessons made the winter season the most comfortable ever. I’m continually amazed at how tangible and immediate the effects of Ayurveda can be.

―― I once attended cooking classes in South India. I learned that, when mixing spices, locals adjust the blends based on their family’s health that day, and even change the ingredients. They didn’t call it Ayurveda, but it really felt like food was naturally integrated with healing; food and medicine originating from the same source.

Yes, I think that’s very true of South Indian food culture. In Sri Lanka, it’s common for families to have several types of medicinal plants growing in their gardens. They use these for cooking and as remedies.

Incorporating Ayurveda into daily life

―― In the cooking classes you lead, how do you recommend incorporating Ayurveda, which originated in India, into daily life here in Japan, where the climate and environment are so different?

My cooking classes run throughout the year, and I teach several simple recipes for balancing the doshas during the five seasonal periods –– spring, summer, autumn, winter and the rainy season. But the dishes aren’t authentic Indian cuisine. They’re very simple –– often there’s just one spice added to a Japanese-style meal.

I also make sure the recipes use ingredients that can be easily found at any supermarket, and I keep the steps easy enough so that students can make them repeatedly through the season. The idea is to make Ayurveda accessible and practical for daily life.

Also, even if you and I experience the same summer season, the way we feel afterward and the changes that occur in our bodies might be completely different. In class, we share those differences as feedback –– how a certain type of person experiences a specific kind of change or how eating something specific or a combination of different kinds of food helped improve a person’s condition. Students not only observe their own body and mind but also learn to understand and observe how the doshas manifest in others.

After about a year of attending the class, students begin to understand how the Doshas influence them. They start creating their own new recipes, adjusting their lifestyles and applying Ayurveda in their own ways. I call my cooking class Mahat Tuning, and by the time students finish the year, they’re able to tune their own mind and body.

Scenes from Mahat Tuning, a seasonal food and lifestyle class led by Hiroko Mihara and Ayurvedic therapist Saki Ikeda.

―― Mahat is not a word I’m familiar with. What does it mean?

Mahat is a Sanskrit word that means great. It refers to a state of being linked to the earth, the cosmos and everything that exists. You could think of it as a kind of universal intelligence — the fundamental energy that supports all life within the universe.

For example: When you plant a seed, its roots grow downward into the soil, and the stem grows toward the sky. Similarly, when a human being is conceived, it grows for ten months in the womb, and as soon as it is born, it instinctively begins to breathe and seeks a mother’s breast. All of these are thought to occur because we are connected to mahat. Humans are meant to be deeply connected to this universal intelligence. The idea is that if our connection to Mahat remains steady, we won’t fall ill and can maintain physical and mental well-being. In reality, our balance can be disrupted by the seasons, our living environment, work, relationships, etc.

The true goal of Ayurveda is to maintain a healthy state for mind and body. I created this class because I wanted everyone to learn to tune themselves to that state. Once the students grasp the theory and begin to put it into practice, they come up with their own ways of applying it. To be honest, I learn a lot from my students, too.

I like to tell them a story. When I return home from a business trip, I always get this intense craving for ramen. It’s not just a vague feeling –– there’s a reason for it. Traveling disrupts Vata (the energy of movement and wind). What soothes an aggravated Vata is warm soup infused with animal fats, so wanting to eat ramen makes perfect sense!

But it doesn’t have to be ramen. Once you understand that, you can achieve the same effect by adding a drizzle of olive oil to miso soup, or ghee (clarified butter). Instead of just mindlessly eating ramen, you realize that you’re feeling fatigued and think about ways of calming your Vata by choosing food that will help. You gain the ability to control and tune your body and mind.

Understanding your body's responses

―― By practicing Ayurveda, can you fix vague discomforts?

I believe so. As with other methods of improving wellbeing, the first step is to identify the reason for the discomfort. Everyone is different, so there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to health that applies to everyone.

My students keep a diary. They write down what they’ve eaten, what they’ve craved, their bowel movements, daily moods. When they look over this record, they can often trace the cause of a discomfort to a specific action or event from a few days earlier. For example, let’s say a student experiences a stuffy nose one day. The student’s diary might reveal a bout of overeating a few days before –– an overindulgence that brought an imbalance in Kapha and led to nasal congestion. Understanding the cause of the discomfort means they can figure out how to take care of it themselves. Ayurveda offers many ways to care for the doshas, so students naturally learn how to manage vague discomforts by adjusting their diet or lifestyle for the season.

―― We hikers usually write a gear list before packing, so we know exactly what we need and how much it all weighs. Everyone has had the experience of packing for a trip, throwing in all kinds of things just in case, and then realizing when they return home that they didn’t use much of it. To avoid that, it’s important to leave out what you don’t need. And to figure out what’s not needed, you have to understand your own skills and experience. If you’re anxious about your abilities, you won’t be able to let go of things.

When people hear Ayurveda, they might be suspicious of the term or lump it in with New Age spirituality. There’s probably some degree of misunderstanding about what it is. Having listened to your explanation, I realize that Ayurveda is a methodical, time-tested system that has been developed over generations.

Yes, exactly. Ayurveda is a methodology for understanding and addressing symptoms and reactions and figuring out an appropriate response.

―― Besides physiology, there’s also something akin to bio-rhythms, right? Your moods fluctuate. Women’s menstrual cycle can have an impact as well. It’s very complex and unique to each person.

Yes. We are all unconsciously influenced by many factors. In Ayurveda, there are also doshas associated with specific times of day. For instance: 6 a.m. to 10 a.m. is Kapha time, 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. is Pitta time, 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. is Vata time, 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. is Kapha time again, 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. is Pitta time, and from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. is Vata time.

So, if you have important decisions to make, you should do them during Pitta time (10 a.m. to 2 p.m.), when that energy is optimal for decision-making. During Vata time (2 p.m. to 6 p.m.), you can use that energy for meetings and communication. Even within the same time frame, the influence varies depending on your dosha. Someone with a Kapha physiology may be more sensitive to the effects of Kapha time.The season and the food you eat also has an impact. The effect these have on your body is complex. But once you begin to understand this framework and how it affects your mind and body, you start to understand how to address problems –– and are less influenced by your moods and health.

【NEXT HIROKO MIHARA “Eating” (2/2)】