HIROKO MIHARA “Eating” #2

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

HIROKO MIHARA “Eating” #2

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

In the HIKING AS LIBERAL ARTS series, hosted by Hideki Toyoshima, Yamatomichi HLC (Hike Life Community) director, we consider hiking as a liberal art, a field of study that liberates individuals from preconceived notions and norms, empowering them to act based on their own values. This series delves into physical aspects of hiking –– seeing, hearing, eating –– for clues to exploring the value of and potential that extends beyond hiking.

This is Part 2 with our third guest of the series, Hiroko Mihara, who runs Nanpūshokudō, a culinary business, with Rika Koiwa. Hiroko is well-versed in shokuyōjō — the practice of nourishing both body and mind through diet –– and her work draws on traditions such as Ayurveda, macrobiotics and Chinese medicine. In Part 1, we began by exploring how eating is linked to our physical and mental well-being and the social fabric that binds us. We continue our conversation by going deeper into Ayurveda and hearing how Mihara’s initiative, Give Me a Vegetable, connects people.

Knowing your digestion capacity: food, emotions, information

―― When you incorporate Ayurveda into your life, it’s not just about preventing illness. It seems to me it could also be used in the opposite way, like improving performance the way athletes do. What are your thoughts on that?

As I mentioned earlier, people are connected to Mahat, the universal life force that keeps us in balance and good health. Within Ayurvedic medicine, there’s also a field called Rasayana, which focuses on rejuvenation –– strengthening health, maintaining youthfulness, boosting immunity and enhancing stamina.

There’s also a concept called Dinacharya, which outlines how to live your daily life in a way that promotes well-being. For example, it recommends waking up 96 minutes before sunrise. This is considered the “purest” time of day. Taking in that energy is believed to be beneficial for the body.

In 2020, during the Yamagata Biennale, we taught a cooking class and created an experimental installation. For the installation, we invited the public to wake up before sunrise and record its effect on body and mind. Among the more than 70 participants from Japan and overseas, some reported positive changes; others found the experience so pleasant that they continued the habit of rising before dawn and taking a morning walk.

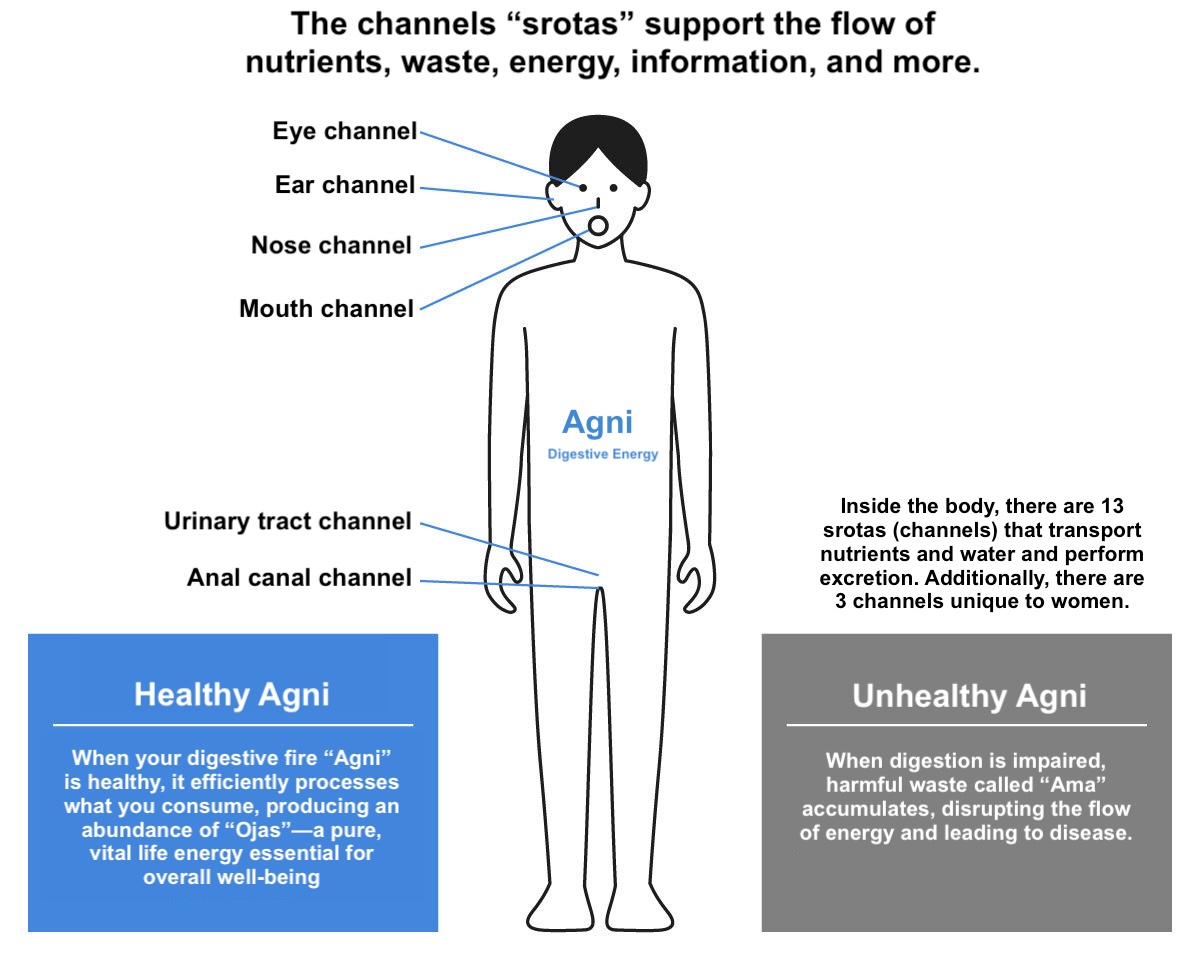

Rasayana comes from Sanskrit: rasa means life essence or flow and ayana means path or route. In Ayurveda, it’s believed that the body contains numerous channels that carry sweat or transport nutrients from food. When these channels become blocked by ama, or undigested substances, that can lead to diseases. It’s extremely important to keep these pathways clear.

By “undigested substances” we aren’t only referring to food. Emotional ama and informational ama exist. Which is why I believe it’s so important to understand what you can truly digest –– physically, emotionally, mentally.

―― Are you talking conceptually when you mention “channels”?

Not at all. A person who is chronically constipated can suffer from colon disease. When someone is under extreme stress, there are signs: higher cholesterol level, thickening blood, rising blood pressure, maybe even clots that cause arteriosclerosis or heart attacks. What happens in the mind has physical manifestations.

―― I see. Earlier, you mentioned the importance of knowing your own digestive capacity. What does that mean?

In Ayurveda, there’s a common idea that the amount of food that fits into your two hands cupped together is an appropriate portion. It’s also important to make sure you’ve fully digested your previous meal before eating again. Ayurveda doesn’t prohibit meat or alcohol, but it does emphasize the importance of eating things when and if you can digest them.

―― So if you’re able to adjust your portion size and time your meal to match your own digestive rhythm, does that mean you can eat anything?

More or less, yes. Different kinds of food have different effects on your doshas. Ideally, you should eat ingredients and flavors that are appropriately seasonal to avoid throwing your doshas out of balance. Realistically, with social situations or family preferences, you can’t always eat according to seasonal guidelines. In those cases, I think what matters most is whether you can digest what you’re eating.

―― How can people tell what their personal digestive capacity is?

I think it starts with being aware of whether you’re actually feeling hungry –– the sensation of an empty stomach. If you’re not getting hungry, it likely means that your previous meal hasn’t been fully digested yet.

There are also ways to make food easier to digest. For example: chewing your food thoroughly, not drinking too much water during a meal and avoiding distractions or doing something else while eating.

In Ayurveda, it’s said that the god of fire, Agni, resides in the stomach. Interestingly, Agni is also the word used to refer to digestive power. When we eat, we are offering food to this inner fire, like a sacred ritual. Eating while multitasking or while standing disrupts Vata, and by focusing fully on your meal, you allow Agni to do its job more effectively.

Applying Ayurveda to mental well-being

―― How does Ayurveda fit in when it comes to being mentally and emotionally healthy?

One concept I mentioned earlier –– not consuming more than you can digest –– also applies to emotions and information.

Taking in more than you can mentally or emotionally process, or “digest”, can lead to feeling depressed or overwhelmed. That’s why it’s important to understand your own capacity and limits; to cut off excess information, to take a step back when you feel you can no longer handle the emotional ups and downs. Once you’re able to process again, you can start letting things back in. I think it’s about giving your body, mind and heart a little breathing room.

One of the practices within Rasayana –– which I mentioned earlier –– is called “behavioral Rasayana”. There are 10 ethical guidelines –– don’t lie, don’t harm others and maintain a healthy balance between work and rest, for instance. I find it fascinating that Ayurveda includes these philosophical principles as part of a healthy life.

The 10 Principles of Behavioral Rasayana

- Speak the truth

- Maintain a lifestyle with a healthy balance between rest and activity

- Act in harmony with the climate and seasons

- Follow a wholesome diet suited to your individual constitution

- Share money, food, knowledge and kindness with others

- Think on a spiritual level

- Refrain from violence

- Avoid anger and aggression

- Don’t indulge excessively in alcohol or sexual activity

- Don’t harm others through words or actions

―― So Ayurveda is actually very scientific: Everything has a logical cause and effect. I was always curious about it but never fully understood it. Now it resonates with me.

Ayurveda’s beginnings are rooted in mythological divine knowledge (*). The ancient scriptures written over a thousand years ago contain mythological elements that are still used by modern Ayurvedic practitioners. These scriptures belong to a storytelling tradition and yet have proven effective for thousands of years. What I find fascinating is that even today, with all our advances in modern science, when we scientifically analyze the teachings of these texts, they still hold up. They make sense.

(*) Ayurveda’s origin story is intertwined with Hindu mythology: Brahma, a major Hindu god, is said to have composed the Ayurveda (before creating humans) and given it to Dhanvantari, the physician to the gods.

Connecting music, food and the body

―― I heard that you’ve often been asked to cook or make bento box meals for musicians, such as Ryuichi Sakamoto and Eye (∈Y∋) from Boredoms. Was there some connection between that and macrobiotics?

The musicians whom I’ve cooked for –– including the two you mentioned –– were all creators of refined, finely tuned music. When I cooked for them, I always purified myself beforehand, chose the freshest ingredients –– ideally free from pesticides and additives –– and focused on enhancing the purity of the food. I used spices and seasonings to make the meal feel exciting or inspiring to eat. I think many of my clients were already very mindful about what they were eating. I don’t know whether their awareness of how food affects the body was in sync with their process of making music.

Let me tell you about one unforgettable experience. I was making bento for Ryuichi Sakamoto while he was working on a soundtrack. On the completed CD, in the inner booklet, he credited not only me as the cook but also a producer of the ingredients. He used the term Sustainable Living Force. That really stayed with me. It taught me that food is a force for sustainable living.

――I’m around people in the art world, where I don’t often hear people talk about macrobiotics or Ayurveda. These seem to be more popular with musicians. The same can be said about musicians being vegetarians and vegans. What are your thoughts on eating meat?

I have two thoughts about eating meat. The first is moral: the recognition that we’re taking a life to eat meat.

At one point, I was asked to develop recipes using the tendons of deer or wild boar –– cuts that restaurants typically avoid. I started paying regular visits to a hunter. I’d previously thought of hunting as a sport –– people using weapons to chase and kill defenseless animals. This hunter I often met was attuned to his mountainous surroundings. Nothing escaped his notice –– he caught the slightest change in a branch’s shape. He was an elderly man, but he sprinted up steep trails like a wild animal. The reality is, the animals that he was hunting fight for their lives –– to the point that it’s possible for the hunter to be injured or even killed by the hunted. It’s a tense and intense life-and-death encounter. Perhaps the hunter didn’t think of it in this way, but seeing how he related to the mountains and animals made it seem as if he considered it an exchange of equals. I was deeply impressed. I still eat meat, but I often think about those moments in the mountains and how I can relate to the things that I consume as equals.

My second thought relates to digestion. Meat requires a lot of energy to digest. The key question is: Do I have the energy to digest it right now? If you eat meat but lack the digestive capacity, it can cause health problems. Let’s say you feel tired and want to eat yakiniku (barbecued beef), thinking that it would help you build up strength. I used to do this when I was younger. But if you go to sleep and there’s still undigested beef in your body, it might be time to reconsider your diet.

The aim of Give Me Vegetable

―― You’re also involved in a project called Give Me Vegetable. Can you explain what it is?

Give Me Vegetable was started by my friend Yoshifumi Ikeda, after the massive earthquake and tsunami in northeastern Japan in March, 2011. He wanted to deliver fresh vegetables and food to disaster-stricken areas. The first event was organized to collect vegetables for that purpose. I started participating from the third event, and after that I joined the team running it.

What’s unique about Give Me Vegetable is that vegetables are the entrance fee. Instead of selling food, chefs cook and serve meals on the spot. At most food events, each vendor has their own booth, and even though they’re next to each another, there’s little interaction. People tend to maintain boundaries so they don’t step on each other’s toes. This event is completely different.

Chefs ask to borrow seasoning from each other and everyone works together, as if they were in the same kitchen. Sometimes, even guests jump in and cook. It feels incredibly free and open and that makes you realize that the boundaries you find at other events are completely artificial. It’s a powerful and refreshing realization. The divide between cooks and diners falls away. That’s the real charm of Give Me Vegetable.

Give Me Vegetable events are staged all around Japan. (Photo credit: Hiroko Mihara)

―― I love the name Give Me Vegetable.

Give Me Vegetable started out as the antithesis to a capitalist society. Along the way, we realized something: substituting vegetables for money doesn’t fundamentally change anything. If you think of money as evil, as something that drives people crazy or controls people, that’s your own invented perception. Money as a tool of exchange is actually very convenient. Money isn’t the issue here. It doesn’t have to be inconvenient or bad. What do you want to exchange the money for? What do you really need? These are the questions that you need to answer.

What makes Give Me Vegetable so special is that anyone of any age can join and enjoy eating delicious food with others. It’s just a fun gathering. Sometimes farmers bring their vegetables and are surprised and delighted by what the chefs make. It’s incredibly peaceful and really shows how good food naturally makes people feel happy.

―― It feels more like community-building than a food event. I think it really reflects the core theme of this conversation: Eating is not just about taking in nutrients, but also forms the foundation of culture and society.

Back when humans were hunter-gatherers, finding food was the most important daily activity. And then everyone shared their food, which connected them as companions. On the other hand, the ones who came to take the food away were enemies. That’s how boundaries formed. So, eating together was the foundation of early social units. It’s also connected to socialization. Meals have always been a way to connect people throughout history.

Today, eating together is an important social event. Negotiations and decision-making in politics and business often take place over a meal –– and the outcomes aren’t always positive. The fact that a meal can influence relationships and societal dynamics hasn’t changed. The same goes for Yamatomichi events –– Yamamichi Festival or Yamatomichi HLC. Hiking. Whether you’re alone or with others feels the same until you reach your destination and connect with someone, which makes the experience enjoyable. It’s the same with eating –– when you share a meal with someone, you also experience shared emotions and moments. Those feelings naturally lead to a sense of community.

Before getting involved with Give Me Vegetable, I was the organizer for an event called One Plate Gathering. You would bring a plate to a park where chefs were cooking, and everyone there would eat whatever was prepared. There were no specific plans or programs. It was a simple gathering, but many new connections were made. There were even couples who met and got married through those encounters. It definitely had a strong community element to it.

Beyond cooking, creating a culinary moment

―― I’ve been following your activities for some time. While you’re obviously someone who cooks a lot, my impression is that you are, above all, a creator of culinary moments –– by which I mean not just a place to eat but, in a broader sense, a space where cooking is the focus. When I curated exhibitions, there were times when I asked you to create art instead of food. I was more interested in the space and community that food fosters rather than simply the act of cooking and eating. I’m curious to know what sort of food you want to create from here on?

The reason I studied food was that I thought of cooking for the people around me, not just for myself. And because of that, I wanted to steer clear of making anything unhealthy. As I went deeper into Ayurveda, I began to understand the thinking behind it, which is when I started incorporating Ayurveda into my cooking. What I realized was that, for 26 years of my cooking career, I had always tried to add elements: incorporate dishes and spices from different countries and experiment with cooking methods for certain vegetables.

But after studying Ayurveda and cooking according to its teachings, my cooking became more stripped-down. When I picked seasonal ingredients, say, a carrot from the supermarket, I would add just one spice and it would be delicious and, as a result, I would feel better. That led me to think about simplifying cooking. I even thought that maybe culinary specialists weren’t needed. I feel that I’ve finally discovered the kind of food that I find truly delicious.

I feel like I’ve always cooked for other people. I cooked for my mother when she was sick. When Ryuichi Sakamoto asked me to make meals for him, I thought carefully about preparing food that wouldn’t place undue stress on his body. Now that he’s passed away, I feel an emptiness. I want to focus more on cooking food that I find delicious; food that reflects who I am and what’s healthy for me.

―― What kind of food do you think that will be?

If I choose healthy, seasonal ingredients, add a bit of spices, herbs or seasonings and eat what suits my digestive capacity, that should be enough to make me happy. The answer to the question of “what is delicious?” might be very simple.

―― Hearing your story makes me feel that eating isn’t only about nutrition but also connecting with your own body and your environment.

That’s right. I’m still learning. But through food, I hope to listen to my body, connect with others and find a balance of both of those things.

Reflections on Hiroko’s story

HIDEKI TOYOSHIMA

I’ve been a vegetarian for about 15 years now, and I’m sometimes asked why I became one. The truth is, there’s no profound reason. My wife happened to be away for a week, and I thought, Why not try having a vegetarian meal today? That’s how it started.

Considering my unhealthy lifestyle until that point, I was terrified of the idea of not eating meat. In reality, though, it turned out to be surprisingly easy. What was supposed to be just one meal continued into the next day, and by the time my wife returned a week later, I had unintentionally become a vegetarian. I’ve basically been a vegetarian since then ––basically because, as the theme of today’s conversation suggests, there’s a social aspect to food.

In Japanese society, it’s relatively difficult to be a vegetarian. It’s manageable when I’m on my own, but not as easy in social gatherings. Most times, there’s almost nothing I can eat, and I either feel miserable or guilty for making everyone go out of their way to accommodate me. What I’ve learned about the types of food that suit me is even more significant than being a vegetarian. This led to my thinking beyond food to what it more broadly means for something to suit me.

That’s the mindset I had as I listened to Hiroko’s story, much of which I was hearing about for the first time or being reminded of. It also helped me re-recognize some things: As we went deeper into food, it felt as though we were talking about ultralight hiking –– when you take both to their logical extreme, you might reach similar underlying principles.

In our discussions about food and wellness, there were nuggets of wisdom that made perfect sense to me. I could even see myself incorporating many aspects into my own life right away. The idea that macrobiotics, Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine’s yin-yang and five elements are all metrics to understand the body and maintain balance aligns with ultralight hiking principles, too. I’m convinced that Ayurveda is based on a scientific body of knowledge accumulated over time. Many hikers would likely find workshops on food tailed to specific body types and conditions quite appealing. I also believe that Eastern methodologies offer a universal truth that connects everything. The starting point and path may differ but we may end up in the same place –– that makes me think that ultralight hiking might be rooted in Eastern methodologies. Finally, my chat with Hiroko made me feel that food should be shared, not fought over –– nutritionally and socially. I can’t wait for the next time when I can cook and enjoy a meal with her.