#5 Hideki Toyoshima (Yamatomichi HLC Project Director)

Photography: Masaaki Mita

#5 Hideki Toyoshima (Yamatomichi HLC Project Director)

Photography: Masaaki Mita

Art and mountains converge

Nearly two decades ago, Hideki Toyoshima stood at the summit of Mt. Aka, in Japan’s Yatsugatake mountain range straddling Nagano and Yamanashi prefectures. During the climb, there hadn’t been much to see. But at 2,900 meters above sea level, Hideki had a view that seemed to extend in every direction: the ridgeline, the distant mountains, the towns at the foot of the slopes and even the faint outline of the Tokyo metropolis. As he took in his surroundings, he experienced a moment of clarity. “It was overwhelming, as if I was seeing the world for the first time,” he said.

Hideki had felt this way before. Not about the mountains but about art. Years earlier, he’d studied at the San Francisco Art Institute, in California, and had created his own performance art. Occasionally he encountered a work of art that had the ability to expand his mind; to shift how he viewed the world. It usually wasn’t the beautiful paintings or impressive sculptures that had this effect on him –– and it had never been the mountains. His epiphany on Mt. Aka was life-altering. “After that, I got completely hooked on hiking and started heading to the mountains almost every week,” he said.

For a while, “the mountains” meant the summit of Mt. Aka. He revisited the place, again and again, as if he were making a fixed-point observation that would, over time, reveal to him changes that only someone who had been there repeatedly would notice. Hiking fascinated him: There was a kind of resonance he felt in every fiber of his body.

Back then, Hideki was producing and curating art as a founding member of graf, a creative and design firm based in Osaka, his hometown. It would be years before he became friends with Yamatomichi’s founder Akira Natsume and got involved in ultralight hiking. But Hideki’s ideas about art, his obsession with the outdoors and his everyday life had already begun to converge.

Hideki’s charming home sits on the outskirts of Makkari, a village in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island.

Art as an event

As a student at the San Francisco Art Institute, Hideki was interested in creating work that was impermanent. It was though a course that he found his preferred form of expression: performance art. Performance art traces its roots to the 1960s’ climate of liberated social, political and sexual mores. “Gradually, I lost interest in making tangible objects as art. I became more attracted to the idea that the event itself is the artwork. That idea connects to the 1960s movement of performance art known as ‘accidents’ or ‘happenings’,” he said.

When Hideki was 20, he created a piece that hinged on a carton of milk and a cup on a pedestal in the center of an all-white room. After cuing the audience, he poured milk into the cup and drank it. Next, he shed his shirt, rubbed the milk on his body, and began doing push-ups while counting aloud. “I would do push-ups until I was trembling with exhaustion. Then my body would heat up and turn red, and my muscles would bulge,” he said.

He called it Milk: It Does a Body Good, after a high-profile 1980s advertising campaign in the US that was funded by the National Dairy Board. Hideki wondered whether the message of ‘drink milk to stay healthy’ was even true. Milk also happened to be the color of an art space: a “white cube” favored for exhibitions. By doing ordinary things — drinking milk, exercising — and surrounding himself in a color symbolizing an art gallery, he was creating art that questioned what should qualify as art. “The act of doing pushups inside a white cube became a sculpture in which the sculptor uses his own body as material,” he said.

The piece proved pivotal for Hideki: It solidified in his mind the value of art as an event.

The view from Hideki’s house: snow stretching to the horizon.

Finding value in experience, not objects

When Hideki starting climbing mountains in 2006, he noticed that the climbing mattered less to him than the going away and returning. Temporarily removing himself from his everyday environment caused an ever-so-slight shift in his surroundings. Hideki remembered feeling something similar as a child when he returned home from a school field trip. Nothing had changed and yet something was different.

He was struck by how much going about his routine influenced his creativity: His creative output seemed a byproduct of his everyday life. “I think the way people handle household tasks and daily routines really reflect their values and creativity. If you pursue that deeply enough, it connects to their entire way of living. I believe how people live is what defines who they truly are, more than their material things or physical traits,” he said.

That’s not so different from the philosophy of ultralight hiking: the experience and how you get around matters more than the gear that you carry.

The nearest public road to Hideki’s hut is 150 meters away, and when it snows, he has to clear a path. Leaving the house unattended in winter isn’t an option.

Life as a form of expression

As a child, Hideki never had a strong sense of ownership over things. When he was in primary school, he went on a fishing trip with a friend. After their lines got tangled and his friend’s rod broke, Hideki dipped into his own savings to buy his friend a new rod. “My parents said, ‘It wasn’t entirely your fault, so you didn’t have to buy it for him, you know?’ For me, it wasn’t about being kind. I thought: If there’s money available, it doesn’t matter whose it is, so why not spend it where it’s needed?” he said.

There were other formative moments from his childhood. Over dinner one night, Hideki’s parents were teaching him a game in which each finger represented a family member –– the thumb was the father, the index finger the mother, and so on. “I suddenly realized, the fingers are separate, but they’re all connected by the palm. Maybe my mom and dad are actually all connected beneath the table. Just like the right and left hand are linked through the arms and the body, maybe even my friend’s family is connected underground. Maybe all people are connected, like one giant living being,” he said.

That sense of cosmic connectedness influenced Hideki’s views about art –– and art taught him to see his own life as a form of expression. “I never really bought into the idea of an artwork having ‘value’ or its price going up,” he said. “The beauty of the piece hasn’t changed –– only the price has. That feels untethered from what really matters.”

Calculating energy resembles making a gear list

These days, Hideki spends much of the year in Makkari, in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island, where he lives in an off-grid house that he and a telemark skier friend, who is a carpenter, built using locally procured materials. The house became a way for him to put the ultralight philosophy to pragmatic daily use.

He first visited the village in 2010, on a ski trip with friends from graf. He had just started skiing but felt like he wasn’t getting any better. A friend introduced him to a local telemark skier, who suggested that Hideki stay for a while and keep at it. Every year after that Hideki’s visits got longer –– a month, then two, then three.

At the time he was living in Fukuoka, on the southwestern main island of Kyushu, and while he had considered moving to Hokkaido, he didn’t want to live too far away from his aging parents in Osaka. Then his parents passed away within six months of each other.

“One day I was chatting with a telemark skiing friend at a gas station in Niseko, (near Makkari), saying maybe I could live here, and the next day he called me up and said, ‘There’s a piece of land available.’ That’s how it started,” Hideki recalled.

He ended up purchasing the 1,000-square-meter plot. The drawback: the property wasn’t hooked up to public water, electricity or gas lines. He tried digging a well, but the water quality was poor. He was ready to give up. At that point, he was traveling and living in his car for a third of the year. If he could do that, what was stopping him from figuring out how to live on his plot, off-grid? “I thought, I could fetch spring water from nearby and maybe get by on electricity from solar panels,” he said.

To figure out whether that was even possible, he calculated his daily energy needs. It was something that he (or any ultralight enthusiast) had a habit of doing before a hiking trip: making a pre-packing list of what he would need. “When I saw the energy numbers, I realized that I might actually be able to make this work,” he said.

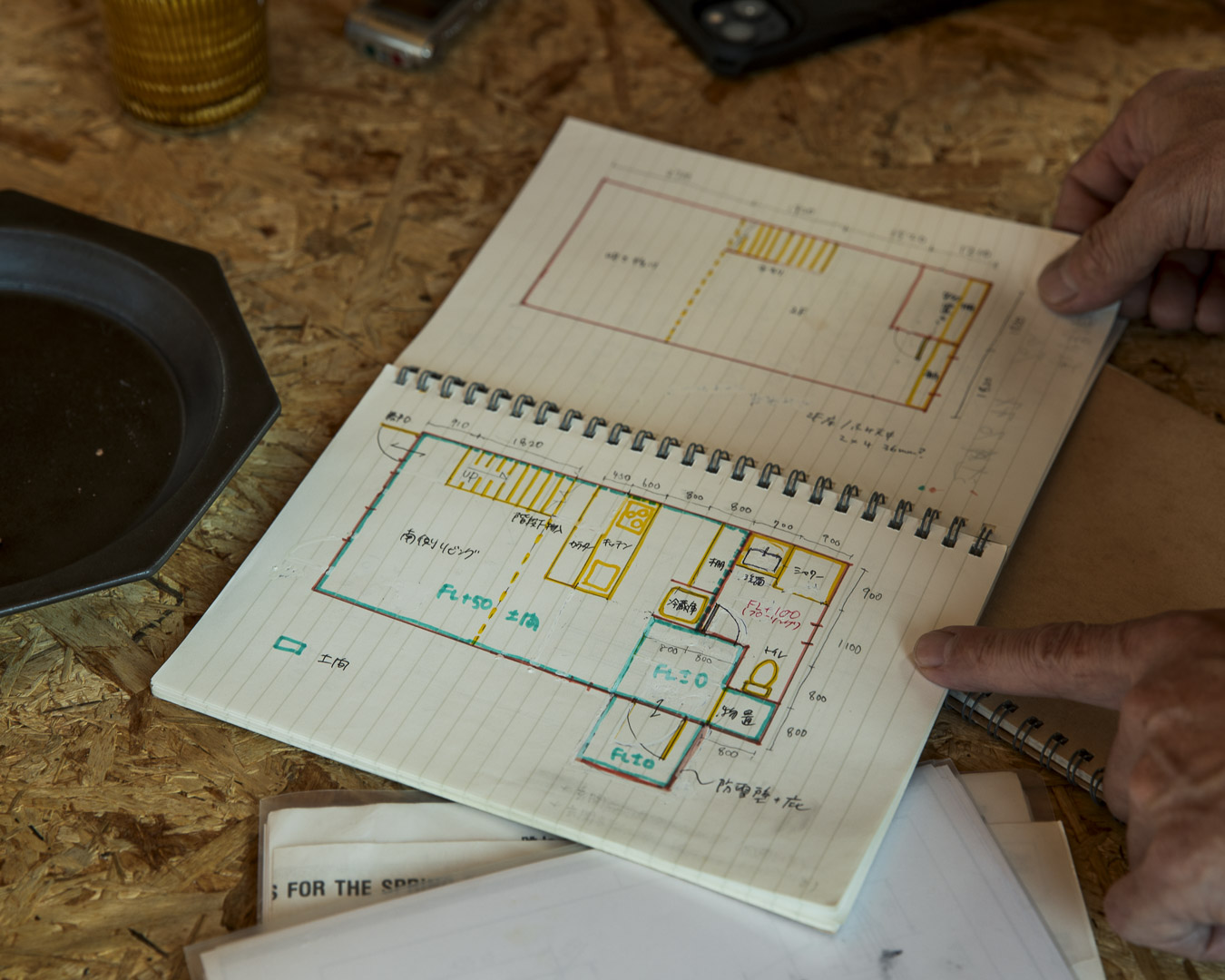

Hideki translated the ultralight mindset into a compact house featuring only the essentials.

A notebook sketch, not a computer-generated blueprint, was the first step. The carpenter decided on-site where to place each pillar.

In Hokkaido, heavy snowfall makes rooftop-mounted solar panels impractical. Hideki’s panels, on the building’s south-facing side, absorb sunlight from above and reflections off the snow — generating more energy in winter than other seasons.

Hideki collects water daily from a nearby hot spring and stores it in a 200-liter tank. A 3,000-watt battery for storing electricity sits beneath the tank. The composting toilet breaks down human waste without needing water.

The ground-floor living room feels spacious, thanks to high ceilings and large windows, and is warmed from sunlight entering the south-facing windows.

In the second-floor bedroom, Hideki uses a cot with a sleeping bag.

The kitchen tiles, arranged in a mosaic style, were leftover pieces gifted by a ski buddy who works in construction.

The storage space under the floorboards has a temperature-regulating fan and functions as a refrigerator.

From telemark skier to home-builder

The idea of living in Hokkaido, the property that he bought after a friend told him about it, the carpenter who taught him house-building skills –– all of that can be traced back to telemark skiing. “For me, saying, ‘I built this house because I was telemark skiing,’ isn’t an exaggeration. It’s actually true,” Hideki said.

Hideki first witnessed someone sashaying down a slope on telemark skis years ago during a late-spring trip to Yarigatake, a mountain range along the border between Nagano and Gifu prefectures. He was shocked: They were nowhere near a resort’s groomed slopes, which he’d always assumed were essential to the sport. It made such an impression that, on his way home, Hideki stopped by a shop and bought himself a pair of telemark skis.

Telemark skiing was invented in Norway in the late 19th century. (The sport is named after Norway’s Telemark region.) It went out of fashion as alpine skiing became popular, but was later revived in the 1970s in the U.S. A decade later, telemark skiers began turning up in Japan. Unlike alpine skis, telemark skis don’t lock the heel, which makes them easier to walk in on flat or uphill sections and is the reason for the sport’s trademark bent-knee style of carving turns on descents.

(Photo credit: Kazushi Ojiri)

The year after the house was done, Hideki built a barn almost entirely by himself. It took time –– he was devoting more hours to the barn than to work –– and it wasn’t exactly cheap. But what he went through and what he ended up learning was well worth the effort. “If you prioritize time or cost, you might be able to do things quickly and inexpensively, but the value of the experience would be lost,” he said. “It’s the same with telemark skiing. In the beginning, you have to spend money on equipment and time to improve your skills. But the rewards are huge. This lifestyle can be quite tough at times. But how you overcome those challenges is incredibly fun –– there’s so much to learn. The experience ultimately enriches your life.”

Summer 2024: The hardest part of building the barn from the foundation was hauling gravel with a wheelbarrow. (Photo credit: Hideki Toyoshima)

Hideki built the barn the same way as the house –– except that for the house he was following instructions. For the barn, he had to figure out a lot for himself. (Photo credit: Hideki Toyoshima)

He finished just before the season’s first snowfall. His two snow blowers (gifts) are among the things that Hideki hadn’t needed for city living.

“In ultralight hiking, there’s a spirit of MYOG (make your own gear). You gain a lot of experience from MYOG,” he said. “I’ve made my own day-hike backpack and turned Tyvek into a tarp and then used them on hiking trips with friends. My barn-building project was an extension of that MYOG mindset.”

A Tyvek tarp Hideki made during a workshop organized by the Kamiyama Hiking Club, in Tokushima, that he’s a part of. The workshop’s aim: connect ultralight hiking concepts to daily work and life. (Photo: Hideki Toyoshima)

Strong winds in the mountains tore the Tyvek tarp, so Hideki used the material to make a day-hike backpack. This was the moment of his MYOG awakening. (Photo credit: Hideki Toyoshima)

The ultralight ethos pervades everything Hideki does. He doesn’t think of daily activities in terms of balancing his work and private life. For him, the two are inseparable, and community plays a key supporting role. This was the message that Hideki conveyed to Yamatomichi’s Natsume during a hike years ago in Senjogahara, a protected marshland in Nikko National Park, in Tochigi prefecture. “Back when Yamatomichi began growing and its products were becoming more popular, the ultralight hiking culture had not yet spread in Japan,” he recalled. “I told Natsume how important it was to create an ultralight hiking culture here. To do that, he needed to foster a community.”

The idea grew into one of Hideki’s enduring initiatives: Yamatomichi Hike Life Community (HLC). Its focus is hiking but it’s become a forum for discussing life and building a sense of community.

Passions, life and community

“I think the ‘hike’ part of HLC can be replaced with whatever a person loves. It can be Surfing Life Community or Food Life Community. The important thing is that the activity is part of the person’s life, and that those have the support of a community. What matters is that there’s an ecosystem,” said Hideki. It’s a reflection of how he’s approached life –– telemark skiing which led to a community which led to buying land in Hokkaido which led to building an off-grid house which represented a fusion of his interests in art and the outdoors. Hideki didn’t have a destination in mind, but he’s arrived at exactly where he wants to be.

Hiker, telemark skier, surfer, art curator, vegetarian, part-time Kyushu resident, part-time off-grid Hokkaido resident. Hideki’s work is an outgrowth of his immersion in two worlds –– art and the outdoors –– and runs the gamut from making videos, writing and editing to serving as an art director and project planner.