#6 The First Steps

#6 The First Steps

Two weeks after arriving in Taiwan, Sasa finally begins what he came for: to walk the length of the island.

From Eluanbi, the southernmost tip, he sets out on foot, following a route that threads through the central mountains—a path less traveled, where forest, farmland, and village life converge.

Along the way, he meets strangers who offer coffee, artists who paint what they see in him, and winds strong enough to test every stitch of his tent. Through each encounter and challenge, the spirit of ultralight deepens—not just as a way of packing, but as a way of being.

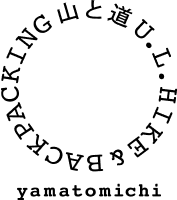

The map

Two weeks after arriving in Taiwan, I finally felt readyto begin my walk across Taiwan.

I had spent days wandering through Taipei, meeting people, and then moved south to Taitung, where the rhythm of life slowed and the air smelled of ocean salt and mountain soil.

Before setting out, I kept asking myself how one even chooses a route through a place so layered and alive. The answer came unexpectedly.

At a middle school concert weeks earlier, I’d met Ruth, a woman whose kindness lingered long after our conversation ended. When we met again, she said, “Takaya, I found something for you. A map drawn by someone who once walked the entire length of Taiwan.”

She handed me the link. The path ran like a spine through the center of the island, cutting between mountains and villages. The moment I saw it, I felt a quiet certainty: this was the way.

I had heard of the “Huan Dao,” the famous cycling route that circles Taiwan. It hugs the coastline, tracing the highway beside the sea. Beautiful, perhaps, but it meant endless asphalt and the sting of ocean wind. I wanted something different.

I wanted to walk where trees closed above me. I wanted to see fields where people still worked the land, to hear dialects older than the cities, to meet the small, surviving cultures tucked inside the folds of the mountains.

The route Ruth showed me promised that. It wound through the center, crossing valleys and remote farmland. It was the kind of road I had been hoping for without realizing it. So I decided to begin at the island’s southern tip and walk north until my body or the land itself told me to stop.

When I returned from climbing Jiaming Lake, I gave myself one quiet day in Taitung. I let my legs rest, visited the weekend market, and ate a familiar vegetarian meal at the small café where the owner always smiled in recognition. I even treated myself to a cheap local massage, the kind that leaves you a little bruised but grateful to be alive.

The comfort of the city, after days in the high mountains, felt like a warm bath. Moving between mountain and town sharpens your gratitude for both. I want to stay that kind of person—someone who can bow to the wilderness and the streetlight with equal thanks.

The man on the bus

The morning I left Taitung, the sky was still pale and soft. I packed my things, checked out of the small guesthouse that had started to feel like home, and boarded a local bus heading south. The seats were cracked, the air thick with the smell of vinyl and sunlight.

Across the aisle sat an older Japanese man with a backpack that looked as worn as mine. We began to talk, the way travelers sometimes do, without plan or purpose. By the time the bus stopped, our conversation carried us into the train station, where we sat together on a long metal bench, waiting for our separate departures.

At one point he stood up and said, “Watch my bag for a moment. I’ll get us breakfast.”

When he returned, he handed me a paper cup. “You drink coffee, right?”

That small gesture caught me off guard. The warmth of the cup, the simple thoughtfulness of a stranger—these things stay with you longer than you expect.

He spoke of his younger years, of the dreams he had once chased and the life he had built instead. He talked about raising children, about work that had both sustained and consumed him, and about how, now that those years were behind him, he was learning to travel lightly again. His voice softened when he spoke of his wife. “She understands this part of me,” he said. “That’s why I can go.”

I listened, quietly moved. He was about my father’s age. Something about his honesty, the unguarded way he spoke of his life, opened a space inside me. I found myself thinking about my own father, about the paths we both walk and the choices that shape them.

Travel sometimes strips away the roles we wear—the job titles, the expectations, even the languages we hide behind. Two strangers, sitting in a station, can speak to each other as if they’ve known one another for years.

Before boarding his train, the man smiled and said, “Let’s meet again somewhere. I’ll be cheering for you.” Then, as if to leave a mark of his own journey, he took out a morin khuur—a horsehead fiddle—and played a slow, echoing tune that filled the platform. Commuters stopped to listen. The sound rose above the noise of the station, a farewell carried on the morning air.

When he was gone, I sat for a while, holding the cooling coffee, letting the moment settle. Some encounters last only an hour, yet they rearrange something inside you. This was one of them.

Later, my own train came. I boarded, pressed my forehead to the window, and watched the fields drift by. Travel by train has a way of pulling thoughts loose, like threads in the wind. I watched the land unroll and felt both small and awake.

By late afternoon, after a few transfers and a final walk along the narrow coastal road, I arrived at the southernmost point of Taiwan: Eluanbi Cape. The air smelled of salt and heat. This was where my walk would begin.

鵝鑾鼻岬のモニュメント。台湾最南端ということで、観光地にもなっている。

It was already past three, too late to start a proper day’s journey, but I couldn’t wait any longer. I tightened the straps of my pack, gripped my trekking poles, and began to walk—retracing the same road I had just arrived on, but now as someone newly in motion.

It felt strange, almost comic, to walk the same path backward. Yet the moment I started, something in me shifted. The road was no longer the same. The act of walking had changed my relation to it. I was no longer a passenger; I was a traveler.

The first steps

It was already close to three in the afternoon, too late to begin a proper day’s walk.

But I couldn’t wait any longer.

I tightened the straps of my pack, gripped my trekking poles, and began retracing the same narrow road I had taken from the bus stop earlier that day. It felt strange, almost comic, to walk the very path I’d just arrived on. Yet the moment I began, something inside me changed. The road itself seemed to change too.

I was no longer a passenger. I was a traveler.

車道のアスファルトの横の芝生がありがたい。

Every step carried a quiet electricity, the body remembering what the mind had been waiting for. With each sound of the poles striking pavement, I felt myself returning to the rhythm I’d known years before on the pilgrim trails of Shikoku. That same awareness—the one that sharpens with every step—came back like an old friend.

Walking has a way of tuning the senses. The noise of cars faded; even the wind became part of a larger hum. Whenever there was a strip of grass or a patch of dirt beside the road, I stepped onto it, just to feel the ground more directly. The difference between soil and asphalt is not only underfoot—it’s in the spirit. The earth receives you; the road merely allows you to pass.

As twilight fell, I entered a resort town along the coast, bright with music and neon signs. Families walked hand in hand, laughter spilling into the night air. For a moment, I imagined stopping to play music there, to open the case of my morin khuur and let its voice join the sound of the waves.

I used to busk when I was younger, standing under streetlights in cities far from home, trading songs for a few coins and stories that stayed longer than the money ever did. The night before, in Taitung, I had met a young Japanese traveler named Ryusuke, playing a handpan in the street. He told me he traveled solely to play, performing every night in a new place. By chance, we were from the same town in Japan, though we’d never met before. Meeting him had stirred something I hadn’t felt in years—the thrill of being exposed to the world, of offering something and not knowing what would return.

Still, I kept walking. I couldn’t find the right spot, or maybe I wasn’t ready to stand still.

As the darkness deepened, my thoughts turned to practical things: if I truly meant to busk along this journey, I would need a chair. The morin khuur isn’t an instrument you can play standing. A chair would make it possible—but it would also mean extra weight.

That small question stayed with me longer than I expected. Once, I would have bought it without hesitation, believing that more possibility was always worth more burden. But years of walking light had changed my sense of value. The philosophy of less is more was no longer about counting grams. It was about space—inside the pack, and inside myself.

When the sky finally darkened, I reached the beach. The air smelled of salt and wind. I was tired, but I didn’t feel like pitching the tent. It seemed intrusive somehow, to stab metal stakes into the sand. So I spread my groundsheet, unrolled my sleeping bag, and lay down under the open sky.

The waves spoke in a slow rhythm beside me. Somewhere between their breath and mine, I drifted into sleep.

Night without a roof.

Morning without walls.

Birdsong woke me in the half-light before dawn. I opened my eyes and saw the horizon glowing faintly red. The sea was calm. The world was quiet.

Without a tent above me, there was nothing between my body and the morning. The first rays of sunlight touched the edge of the water, and for a brief moment, I felt what it meant to wake fully inside the world.

The painter and the chair

The next morning, I packed my things and started north along the coast. The wind was stronger than the day before, pushing hard against my shoulders. My breakfast was simple: instant coffee mixed with butter powder from Japan, brewed on a small alcohol stove. The taste was familiar, comforting, a small ritual of order in a life that had become mostly motion.

By midday, I reached a small town. The streets were quiet except for the sound of scooters and the rattle of shop shutters. The wind eased as I walked between the buildings, and I felt a wave of relief.

Then I saw it—a hardware store with a cluttered display spilling out onto the sidewalk. I thought, Maybe they’ll have a folding chair. Inside, the shop smelled of metal and dust.

The woman at the counter smiled and pointed to a shelf near the back. And there it was—the exact chair I had imagined: light, collapsible, simple. I picked it up and turned it over in my hands, hesitating. Would I really carry this all the way across Taiwan? She left me alone to think, quietly sweeping the floor.

買った折りたたみ椅子と馬頭琴

Nearby, a woven bamboo hat caught my eye—a broad, pale circle, like something a monk might wear while walking. I remembered the pilgrims in Shikoku, white robes bright against the fields. I smiled, thinking it might keep the sun off my face.

In the end, I bought both. I laughed at myself as I stepped outside, the same man who had just spoken so proudly of less is more. Yet I couldn’t help feeling a small lift of joy. Sometimes a new item changes your spirit more than your load.

The road led through farmland in the afternoon, fields of pineapples and papayas stretching in orderly rows. The hat shaded my eyes, but the wind caught it again and again until I had to tie it down with string. Freedom always seems to come with a bit of inconvenience.

As I entered the next town, a sign caught my attention: “Calligrapher’s Vegetarian Café.” My stomach answered before my mind did. I peered inside.

The walls were covered not with calligraphy but with paintings—wide, quiet landscapes in oil. A man appeared from the back, smiling. “Sorry,” he said in Mandarin, “we’re closed today.”

I told him the paintings were beautiful, and his smile deepened. “I made them,” he said, then waved me in anyway. A few minutes later his wife returned and greeted me in simple Japanese, enough for us to bridge the gaps between our languages. She poured tea and brought out fruit, and soon we were talking as though we had known each other for years.

When I told them I painted as well, the man’s eyes brightened. “Wait,” he said, already walking toward the door. “Come, I want to paint something now.”

おじさんのアトリエ(?)にて。頭の中のイメージだけで筆を振っている。キャンバスを何度も塗りつぶして使っていたり、段ボールでもなんでも画材にしていたりと自由だった。

He led me outside to his small studio, a garage filled with brushes and half-finished canvases. “Meeting you made me want to paint,” he said, already reaching for his tools. “Let’s see what comes.”

He began to work immediately. His hands moved fast, certain, as though the image already existed somewhere inside him. The air in the room shifted; everything became still except for the sound of the brush against canvas.

After about an hour he stepped back. “Maybe like this,” he murmured. The trance on his face softened into a smile. “I paint one in the morning and one at night, every day,” he said. “Always whatever scene rises in my heart. Today, after meeting you and talking, this is what came.”

He gazed at the painting with quiet satisfaction. I stood beside him in silence, feeling the warmth of his joy.

ぼくのために描いてくれた今日の1枚と一緒に記念撮影。

Before I left, his wife poured more tea, and we spoke a little longer. I told them I’d return another day to eat there when the café was open. I thanked them both and said goodbye.

Outside, as I walked past the gate he had painted, I realized how much this brief encounter had filled me. It was one of those small gifts that walking brings—meetings that ask for nothing and give everything.

The wind

By the time afternoon came, the wind had changed. It swept across the coast with a steady, heavy strength, bending trees and pushing against my shoulders. The bamboo hat I’d bought only the day before turned out to be a poor choice for such weather. No matter how I tied it, the wind caught it like a sail. In the end, I gave up and fastened it to my pack.

I walked until the sky began to dim. The light along the coast turns gold just before it disappears, and everything—sand, sea, even the air—seems to glow. When darkness came, I found a patch of forest behind the dunes. The trees grew close together, enough to block the worst of the wind, and I set up my tent there.

I was careful that night, placing large stones over the tent pegs and tightening every line. The air hummed with wind. The sound of it moving through the trees was like a tide.

Later, when I was half-asleep, the gusts grew stronger. The tent snapped and shuddered. The trees above creaked as if they might break. I remembered a night many years ago in the United States when a hurricane tore through my camp and shredded my tent. I had walked for days afterward with only half of it left, feeling exposed and grateful at once.

That memory returned sharply. If the tent went now, the journey would change completely. I sat up and decided that sleep could wait. I lowered the poles to make the tent flatter against the ground and weighted the edges with more stones. The fabric pressed down close over me. It felt like crawling inside a thin shell, but it worked. The tent held.

At some point, I drifted off. When I woke again, it was still dark, maybe four in the morning, and the wind hadn’t stopped. I lay there listening. The noise was endless, but there was a rhythm to it, a pulse like breathing. I thought, If I’m going to wait this out, I might as well move.

So I packed in the half-light and stepped out into the cold air. The wind met me instantly, pushing hard from the front. But walking gave it purpose. It’s easier to face resistance when you’re moving through it.

The road followed the shoreline. For hours I walked through the gusts, the salt stinging my face. Around noon the wind finally softened. I found an open space overlooking the sea and stopped to rest.

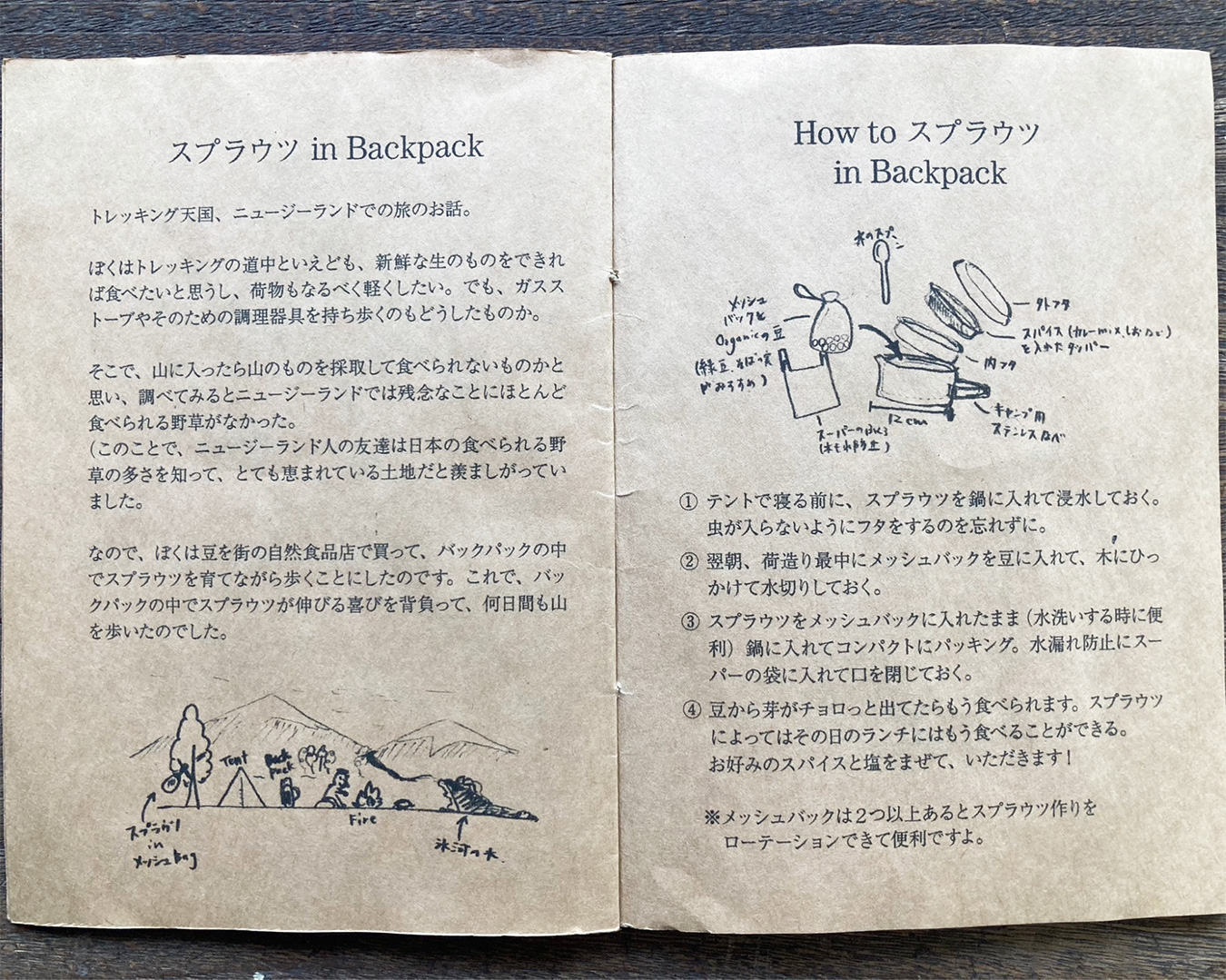

Sprouts in the backpack

For lunch I ate the sprouts I’d been growing inside my pack—mung beans and millet, or maybe foxtail millet; I could never tell. They had been germinating since the night before, turning quietly into food as I walked.

Sprouting is simple, and it fits a traveler’s life.

Here’s how I do it:

- Before sleeping, soak beans or grains in your cooking pot.

- In the morning, while packing, drain them and move them into a mesh bag.

- Hang the bag from a branch to let it drip-dry.

- Once it’s no longer wet, tuck it into a ziplock or pot and place it in your backpack.

The warmth and darkness inside a pack are perfect for sprouting. By the next afternoon, the beans are alive, crisp, and ready to eat. Before lunch, I rinse them once more, add a little salt, maybe a pinch of spice or some dried fruit.

歩行中のバックパックは、ちょうど良い暗さと保温性の、スプラウツにはばっちりの環境で、豆の種類によっては、昼過ぎには発芽して食べられる状態になります。食べる前にもう一度水ですすぎ、塩やスパイス、ドライフルーツと一緒に食べるのがお気に入りです。

スプラウツした状態。豆の種類では、緑豆や蕎麦の実が好みだ。

I came up with this method about fifteen years ago in New Zealand, while “tramping,” as trekking is called there. At the time, I was deeply into raw food. Whenever I found a farmers’ market, I would buy piles of fresh, local produce and carry it in my backpack—fruit, greens, whatever looked good. It was glorious for a day or two, until the weight and the bruising taught me otherwise. That’s when I began experimenting.

Sometimes I made sauerkraut from shredded cabbage, massaged with salt and sealed in a ziplock. It fermented as I walked, staying fresh for days. But more than once, the brine leaked through my pack, leaving everything soaked in the smell of cabbage and vinegar. Lesson learned.

Among all the raw-food experiments, sprouting turned out to be the best idea of them all. Dry beans take up almost no space, yet once soaked, they multiply several times in size. They’re light, nutritious, and need no fire. A single small bag can feed you for days.

That said, I’ll be honest—sprouts aren’t exactly delicious. On the trail, eating them every day, I start to get tired of the taste. They’re powerful food, too; eat too many and they sit heavy in your stomach. This time, the beans swelled more than I expected after soaking. I ended up eating too much and spent the rest of the afternoon feeling slightly sick.

Still, the method works. It’s a simple kind of magic—food that grows quietly while you move.

2012年に作った冊子『TABI食堂 食べられる都会の森』。

冊子の中身。スプラウツさせるもうひとつの利点は、生食でなく加熱して食べる場合も、豆や米を浸水することで火にかける時間が短くなり、ガスや燃料の節約になること。発芽させると栄養価も上がるようですよ。

That evening, I reached a small town I’d passed through two days earlier. It felt familiar, though I’d only seen it in passing. There’s a strange comfort in returning somewhere you’ve already left—it reminds you that the world has shape, even when your days are unanchored.

By then, the sky was dark and my body was spent. I decided to find a place to stay rather than camp again. I searched on my phone and found a small inn on the edge of town.

Letting go

That night, I found a small inn on the edge of town. I’d walked until my legs were trembling, and the thought of a bed felt like a gift.

I slept for ten hours straight. The kind of sleep that pulls you under without dreams. When I woke, the light through the curtains felt soft, almost kind. For the first time in days, the world was still.

I lingered in the room that morning, taking my time. After breakfast, I unpacked everything and spread it across the floor. It felt good to see it all at once—the sum of what I’d been carrying. When you walk every day, even small weights start to matter.

I decided to let go of anything I hadn’t used.

Somewhere along the way, my mindset had changed. I used to enjoy collecting things when I traveled—picking up small objects, adding something new wherever I went. Now the impulse had reversed. I felt drawn toward subtraction instead of addition.

The question had become: How light can I travel and still feel whole?

I poured out the alcohol I’d been carrying for my stove. It had seemed useful when I packed it, but I hadn’t used it once. My mornings were fine with cold instant coffee. Simplicity had started to feel like its own kind of comfort.

宿に泊まると、色々な人と会えるから楽しい。仲良くなった高校生のロベルトは、長期休みを利用して、先述の台湾一周「環島」の自転車旅をしていたところ。彼のような現地の若者の話をたくさん聞けたことが、大変勉強になった。

That day’s path wound through endless farmland—fields of pineapples, papayas, and mangoes. The colors looked painted on, the air heavy with fruit.

By dusk I reached the town where I had planned to meet Ak, a Taiwanese friend I’d first met on the climb to Jiaming Lake a week earlier. We’d spent those mountain days together, trading stories about our homes and promising to meet again once my walking journey began.

今日の道は、パイナップル、パパイヤ、マンゴーなどなど、単一農業の大きな農地を抜ける道。まるで屏風画の中を歩いているような気分だった。

Seeing him there waiting felt like closing a small circle. The road, which had been silent for days, suddenly had a voice again.

He took me to a small local restaurant, the kind with handwritten menus and steam on the windows. The food was simple and full of care—rice, vegetables, soup. Ak ordered extra dishes for me to try, explaining each one with quiet pride.

休日のアクと食堂にて。ふたりでお腹いっぱいいただきました。

We ate until we were full. It was a joyful evening, the kind that feels both ordinary and rare when you’ve been alone for a while.

Later, walking back through the warm night, I thought about how this journey was already changing me. I had started wanting to see Taiwan’s landscapes, but what I was really discovering was how to move with less—less weight, fewer wants, and a clearer heart.

Every day, something is gained and something is given back.

Maybe that’s what walking really teaches: how to keep going, a little lighter each time.

Born in Tokyo in 1979, Takaya Sasa has traveled through more than 60 countries, learning from life on the road—whether through cooking, music, shoemaking, or other crafts.

In 2013, he relocated to the banks of the Shimanto River in Kochi Prefecture, Japan, where he began building a lifestyle rooted in the land.

In 2016, he published The Salad Book (ささたくや サラダの本), a collection of raw food recipes and travel essays. He began creating pastel artwork in the summer of 2020, and in 2023, he self-published two books: TABI no Ohanashi-kai, a collection of travel stories, and Kurashi no Kage, a visual diary of daily life along the Shimanto.